Spinors, Dirac Operators, the $\widehat{A}$-Genus, and its Refinement

Published:

Let $M$ be an oriented smooth $n$-manifold; then there is a a coherent way of choosing oriented bases on $T_x M$ for every $x \in M$. If we choose a metric, then we can make these orthonormal bases and hence, we get a principal $SO(n)$-bundle called the orthonormal frame bundle (the isomorphism class is independent of metric). A spin structure is a choice of principal $\text{Spin}(n)$-bundle which is a lift of the orthonormal frame bundle. This structure group can be thought of as the even units in the Clifford algebra $Cl_n$ and provides us with an action. The obstruction to a spin structure is the cohomology class $w_2(M)$ so we say $M$ is spinnable if $w_2(M)=0$. It turns out that spin structures are parametrized by $H^1(M,\mathbb{Z}/2)$.

If a closed Riemannian manifold $(M,g)$ is equipped with a spin structure, we can define a Dirac operator $D$ on the spin bundle which is composed of a spin connection (unique lift of the Levi-Civita connection of $g$) and Clifford multiplication. This $D$ is elliptic, acts on sections of the spin bundle, and solutions $D\psi = 0$ are called harmonic spinors. We may think of $D$ as a “square-root” of the Laplacian; in a way, we can also think of the spin bundle $S$ as a “square-root” of the frame bundle in that $S \otimes S^* \cong Cl(TM,g)$, the Clifford bundle.

The Atiyah-Singer index theorem tells us that the index of the operator is equal to a topological invariant: $\text{ind}(D) = \widehat{A}(M)$. The $\widehat{A}$ genus can be defined for any manifold without any reference to Dirac operators and is usually just a rational number. But if $M$ is spin, then $\widehat{A} \in \mathbb{Z}$. Indeed, this is the history: Atiyah noticed that the $\widehat{A}$ genus is an integer in the spin case and wanted to know why it is an integer. He suspected that it is the index of some operator.

For context, here’s the general definition of $\widehat{A}(M)$ using rational polynomials in Pontryagin classes which exist for any smooth oriented manifold. It comes from the power series: $Q(z) = \frac{\sqrt{z}/2}{\sinh(\sqrt{z}/2)}=1-\frac{z}{24} + \frac{7z^{2}}{5760}-\cdots$

For a manifold, the Pontryagin classes vanish after a certain degree so the series terminates, and we integrate the terms on the manifold (this is why we need an orientation). For example, in dim 8, $\widehat{A} = \frac{1}{5760}(-4p_2 + 7p^2_1)$. Because Pontryagin classes exist in degrees $4i$, then this invariant is possibly nonzero only for manifolds of dimension $4n$. The $\widehat{A}$-genus is additive (connected sum) and multiplicative (Cartesian product) so we actually have a graded ring map $\Omega^{SO}_* \to \pi_*(KO)\otimes \mathbb{Q}$. Here, $KO$ refers to real K-theory which we’ll explain more of later but for now, it suffices to know that after tensoring with the rationals, this graded ring is $\mathbb{Q}$ exactly in degrees $4i$ which fits the bill of what we want.

Anyways, using Atiyah-Singer, we have the index relationship. On the other hand, the Lichnerowicz–Weitzenböck formula says that for a spinor $\psi$, $D^2 \psi =\nabla^* \nabla \psi + \frac{1}{4} s \cdot \psi$ where $s$ is the scalar curvature (a function: $s:M \to \mathbb{R}$). Suppose that $M$ admits a metric with positive scalar curvature and also has a harmonic spinor $\psi$; that is, $D \psi = 0$. Then the Laplacian $\Delta \psi := \nabla^* \nabla \psi = -\frac{1}{4} s \cdot \psi$. This means that $\Delta$ has a negative eigenvalue. But on closed manifolds $M$, the spectrum of the Laplacian is bounded below by $0$. So in fact, there cannot be any harmonic spinors on $M$. This implies $\dim \ker D = 0$. Then, the index $\text{ind}(D) = \dim \ker D - \dim \text{coker} \, D = 0$. This is because $D$ is Fredholm which implies that $\text{coker} \, D = (\ker D^*)^\perp$. Furthermore, $D$ is self-adjoint.

NB1: There is an interesting question on mathoverflow which asks if there is a way to prove this result without the index theorem and the LW formula. The first answer suggests that knowing that $\widehat{A}$ is an integer and also having Chern-Weil theory is not enough. The answer considers some of the work of Gromov on curvature and ends with the following: “Philosophically, integrality is too global to capture the spin condition and Chern-Weil theory is too local to capture the sign of the curvature.”

NB2: The $\widehat{A}$ genus cannot be used to detect whether exotic spheres admit positive scalar curvature metrics. However, a “refinement” called the $\alpha$-invariant can give some answer as shown in the work of Gromov-Lawson and Stolz. This $\alpha$ will be the subject of much of our later discussion. The reason that $\widehat{A}$ is insufficient is because for any sphere, it vanishes for topological reasons. Pontryagin classes vanish automatically for spheres which do not have dimension $n=4k$. When $n=4k$, the only possibly nonvanishing term is a multiple of the top Pontryagin class. But it also vanishes since the signature, another genus expressible as a rational polynomial in Pontryagin classes, vanishes.

Theorem (Gromov-Lawson): Let $M$ be a simply connected manifold of dimension at least 5:

- If $M$ is not spin, then $M$ admits a positive scalar curvature metric.

- If $M$ is spin and spin cobordant to a manifold with p.s.c metric, then $M$ also has such a metric.

Theorem (Stolz): If $M$ is a simply-connected spin $n$-manifold of dimension at least 5, then $M$ admits a metric of positive scalar curvature if and only if $\alpha(M)=0$.

This $\alpha$ is a spin cobordism invariant and takes values in $\mathbb{Z}$ if $n \equiv 0 \pmod{8}$, in $\mathbb{Z}/2$ if $n \equiv 1,2 \pmod{8}$, in $2\mathbb{Z}$ if $n \equiv 4 \pmod{8}$, and vanishes in all other cases; it agrees with $\widehat{A}$ in dimensions $4n$ (up to some factor). I’ll discuss more of this below but note that the mod 8 patterns here seem pretty close to that of Bott periodicity.

The situation is more complicated in the presence of a nontrivial fundamental group (see this article). Let $Z^\pi_m$ be the Grothendieck group of finitely generated $\mathbb{Z}/2$-graded modules over the Clifford algebra $Cl(\mathbb{R}^m)$ which have a $\pi$-action commuting with the Clifford action. The inclusion $Cl(R^m) \subset Cl(R^{m+1})$ induces a dual pullback $i^*:Z^\pi_{m+1} \to Z^\pi_m$. The real $KO$-theory groups of $\mathbb{R}[\pi]$ are given by: $KO_m(\mathbb{R}[\pi]) = Z^\pi_m/i^*Z^\pi_{m+1}$.

Rosenberg defined a $KO$-theory-valued invariant $\alpha$ taking values in this group which generalizes the $\widehat{A}$-genus. This invariant is defineable as a morphism $\Omega^{\text{Spin}}_* \to KO_*$ which sends $[M]$ to the index of the Dirac operator modulo 2 if $n \equiv 1,2 \pmod{8}$. One reference is this article on Manifold Atlas or Lawson & Michelsohn’s book.

It was conjectured that this might provide a complete description of the obstruction to the existence of a metric of positive scalar curvature; this refined conjecture became known as the Gromov–Lawson–Rosenberg conjecture.

Stolz Conjecture

Before getting to the $\alpha$-invariant, let’s write down the above theorem and take a brief detour: Let $M$ be a closed, spin manifold admitting a metric with positive scalar curvature. Then $\widehat{A}(M) = 0$.

There is a conjecture of Stolz which says: Let $M$ be a closed, string manifold admitting a metric of positive Ricci curvature. Then the Witten genus vanishes.

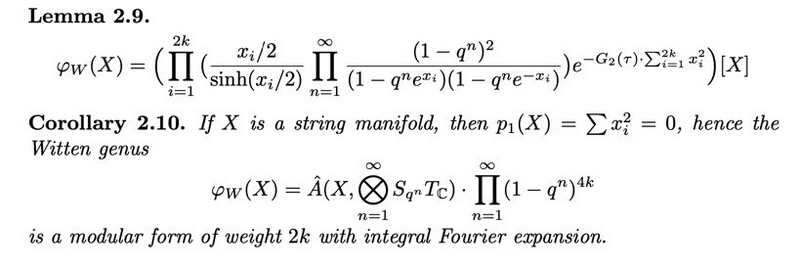

What is the Witten genus? It is a modular form valued cobordism invariant on string manifolds made up from twisted $\widehat{A}$ genera. We can also prefer to think of it as direct quantization of $\widehat{A}$, particularly because of the $\dfrac{(x/2)}{\sinh(x/2)}$ and the $q$’s as seen in this lemma below. Interestingly, the Witten genus is a modular form.

$\alpha$-Invariant

In order to understand the $\alpha$-invariant, I will need to define things more carefully. Recall that if $E\to X$ is an oriented real bundle over a compact smooth $n$-manifold, it has structure group $SO(n)$ if we also pick a metric. Then we may ask if there are lifts of the bundle to a bundle with structure group $\text{Spin}(n)$. If $n=2m$ is even then, there is a unique irreducible complex spinor bundle $S_\mathbb{C}(E)$ which splits into a direct sum $S_\mathbb{C}(E)=S_\mathbb{C}^+(E) \oplus S_\mathbb{C}^-(E)$ of $Cl^0(E)$ modules (this Clifford algebra is generated from an even number of elements of $E$). The way to get this splitting is to take $Cl(E)\otimes \mathbb{C}$ and the global section of it $\omega$ which is given at a point $x\in X$ by $i^m e_1…e_{2m}$ (Clifford product) for any positively oriented orthonormal basis of $E_x$. For any $e \in Cl^1(E)\otimes \mathbb{C}$, we have that $e\omega=-\omega e$ and also that $\omega^2=1$. We let the bundles $S_\mathbb{C}^\pm(E)$ be the $\pm 1$-eigenbundles obtained from multiplying by $\omega$.

When $n \equiv 0\pmod{4}$, there is an analogous construction in the real case. Let $S(E)$ be the irreducible real spinor bundle of $E$ and let $\omega$ be a section of $Cl(E)$ by setting it, at $x \in X$ to be $e_1…e_n$ for any positively oriented orthonormal basis at $x$. The same relations as above hold: $\omega^2=1,e\omega=-\omega e$; it is necessary that $n$ is a multiple of 4 for these relations to hold.

We then define $S^\pm(E)$ as the $\pm 1$-eigenbundles obtained from multiplication by $\omega$. If $n\equiv0 \pmod{8}$, then $S^\pm (E) \otimes \mathbb{C} = S^\pm_\mathbb{C}(E)$; we see that in these dimensions, the two complex representations arise as complexifications of real representations. If $n \equiv 4 \pmod{8}$, then $S^\pm(E)\otimes \mathbb{C} \cong S_\mathbb{C}^\pm(E) \oplus S_\mathbb{C}^\pm(E)$ and so the in these dimensions, the representations are actually quaternionic.

Next, let $D(E)$ be the unit disk bundle and $\partial D(E)$ denote the unit sphere bundle. Then $\pi:D(E) \to X$ is the projection. If $n=2m$, then the pullback of the spinor bundles to $D(E)$ are canonically isomorphic on the sphere bundle $\partial D(E)$: $\mu:\pi^* S_\mathbb{C}^+(E) \to \pi^* S_\mathbb{C}^-(E)$. This isomorphism is defined at a point $e \in \partial D(E)$ by Clifford multiplication: $\mu_e(\xi) = e \cdot \xi$. Since $e \cdot e = -|e|^2$, $\mu$ is invertible and hence an isomorphism.

Thus, if we let $Th(E)$ be the Thom space of $E$ (or view it as a pair of spaces), then the pair of bundles give a difference element $\eta_\mathbb{C}(E)=[\pi^* S_\mathbb{C}^+(E),\pi^* S_\mathbb{C}^-(E),\mu] \in \widetilde{KU}(Th(E))$ in reduced complex K-theory. Remember, we think of $KU^0$ as containing formal differences of complex vector bundles.

If we have $n \equiv 0 \pmod{4}$, then we can follow the real discussion and get an element of reduced real K-theory $\widetilde{KO}(Th(E))$.

Now, let $\mathbb{E}_{8k}$ be the universal $8k$-plane bundle over $B\text{Spin}(8k)$; it is defined as follows. We have the double cover $\text{Spin}(n)\to SO(n)$ for any $n$ and a universal bundle $ESO(n)\to BSO(n)$ which pulls back to $B\text{Spin}(n)$; this is what we call $\mathbb{E}_{8k}$. Then, let $\eta(\mathbb{E}_{8k}) \in \widetilde{KO}(M\text{Spin}(8k))$ be the difference element defined before for this Thom space (which in this special case is called $M\text{Spin}(8k)$). When $n$ is fixed and $k$ large enough, there is an isomorphism between the spin bordism group $\Omega^{\text{Spin}}_n \cong \pi_{n+8k}(M\text{Spin}(8k))$ which means that a spin cobordism class $[X]$ determines a map $f_X:S^{n+8k} \to M\text{Spin}(8k)$. We can define a group morphism $\alpha:\Omega^{\text{Spin}}_n \to KO^{-n}(pt)$ by sending $[X] \mapsto f_X^*\eta(\mathbb{E}_{8k}) \in \widetilde{KO}(S^{n+8k}) \cong \widetilde{KO}(S^n) = KO^{-n}(pt)$. The penultimate isomorphism is by Bott periodicity and the last one is by suspension isomorphism and recalling that reduced K-theory of $S^0$ is the same as usual K-theory of a point. The invariant $\alpha(X)$ agrees with the $\widehat{A}(X)$ invariant up to a factor of $1/2$ in dimensions a multiple of 4. In fact, the spin cobordism groups form graded rings with Cartesian product and the real K-theory also forms a graded ring which we geometrically interpret as operations of vector bundles. Thus, we actually have a graded ring morphism $\alpha:\Omega^{\text{Spin}}_* \to KO^{-*}(pt)$.

Example: Let $M,N$ be smooth spinnable $4k$-manifolds and $H^1(N,\mathbb{Z}/2) =0$. Then $H^1(M\#N,\mathbb{Z}/2) = H^1(M,\mathbb{Z}/2)$ by Mayer-Vietoris so there is still the same number of spin structures. However, if $\alpha(N) > 0$, then we can have more connected sums, say, $\ell$ of them: $Q:=M \# N \#…\# N$ without changing the number of spin structures but $\alpha(Q) = \alpha(M) + \ell \alpha(N)$ grows as $\ell$ grows. Of course, the underlying topological and smooth manifolds are changing.

Let’s recall the ring structure of $KO^{-*}(pt)$. Let $\eta$ be the generator of $KO^{-1}(pt) =\mathbb{Z}/2$ (the Hopf bundle class), $y$ the generator of $KO^{-4}(pt)=\mathbb{Z}$ (quaternionic line bundle), and $x$ the generator of $KO^{-8}(pt)=\mathbb{Z}$ (the Bott element). Then $KO^{-*}(pt)$ as a ring is $\mathbb{Z}[\eta,y,x]/\langle 2\eta,\eta^3,\eta y,y^2-4x \rangle$.

Theorem (II.7.10 in Lawson-Michelsohn): Let $X$ be a compact spin $n$-manifold. When $n\equiv 1,2 \pmod{8}$, let $H = \ker(D)$ be the kernel of the Dirac operator which is the space of real harmonic spinors. Then the index of the Dirac operator is

\[\text{ind}(D_X) =\alpha(X)= \begin{cases} \dim_\mathbb{C} H \pmod 2 & n \equiv 1 \pmod{8} \\ \dim_\mathbb{H} H \pmod 2 & n \equiv 2 \pmod{8} \\ \frac{1}{2} \widehat{A}(X) & n \equiv 4 \pmod{8} \\ \widehat{A}(X) & n \equiv 0 \pmod{8} \end{cases}.\]So we have a way to compute the $\alpha$-invariant using the index of Dirac operators, the target these land in matches Bott periodicity, and we see that it coincides with the $\widehat{A}$-genus (up to a factor) in dimension $4k$. We also restate: for homotopy spheres of dimension $4k$, the signature and $\widehat{A}$-genus are rational combinations of Pontryagin numbers. Since there is only the top Pontryagin number for homotopy spheres and the signature is 0, then so is the $\widehat{A}$-genus. This also means that the index of the Dirac operator for homotopy spheres in these dimensions is 0. Because the theorem tells us $\alpha$ is a multiple of $\widehat{A}$ in dimensions $4k$, then both are zero for homotopy spheres in those dimensions and thus, they admit positive scalar curvature metrics (using a theorem of Stolz we’ll state below).

Let’s see why it is that compact spin manifolds that admit positive scalar metrics not only have vanishing $\widehat{A}(X)$ but also vanishing $\alpha$. Hitchins observed that $\alpha(X)$ is an obstruction to $X$ admitting a positive scalar curvature metric. Consider the Bochner–Weitzenböck formula for the square of the Dirac operator $D^2 = \nabla^* \nabla + \frac{1}{4}s$, where $s$ stands for the operator which multiplies by the scalar curvature function. Since the connection Laplacian $\nabla^* \nabla$ is a positive operator, it follows that $D^2$ is a strictly positive operator if $s > 0$. In that case, one has $\ker D = 0$ and this implies, by the theorem above, that $\alpha(X) = 0$. So when manifolds are not simply connected, we don’t have an if and only if but we have at least one direction.

One might ask whether there are exotic spheres which have a non-trivial $\alpha$-invariant. This question is answered in the affirmative by Adams and Milnor, whose contributions together show that the $\alpha$-invariant constitutes a surjective group homomorphism from the group $\Theta_n$ of homotopy $n$-spheres (with addition induced by the connected sum operation) onto the group $\mathbb{Z}/2$, provided $n \equiv 1, 2 \pmod{8}$ and $n \geq 9$.

Before discussing this, recall that homotopy spheres with $n \geq 2$ have unique spin structures and are also stably parallelizable (admit stable framings). Indeed, stably framed manifolds are also spin. Moreover, the homotopy spheres form a group $\Theta_n$ under connected sum. So we have the following sequence $\Theta_n \to \Omega^{fr}_n \to \Omega^{\text{Spin}}_n \to \Omega^{SO}_n$. For example, with $n=7$, $\Theta_7 =\mathbb{Z}/28$ whereas $\Omega^{fr}_7$ is isomorphic to the stable homotopy groups of sphere $\pi^S_7 =\mathbb{Z}/240$. Lastly, Thom showed that $\Omega^{\text{Spin}}_7 = 0$. Moreover, the image of $\Theta_7 \to \Omega^{fr}_7$ is trivial because all 28 exotic 7-spheres bound parallelizable 8-manifold and thus, are framed cobordant to the standard 7-sphere. It is also known that in the sequence $\Omega^{fr}_n \to_f \Omega^{\text{Spin}}_n \to_g \Omega^{SO}_n$, $\ker g$ is nontrivial only for $n\equiv 1,2 \pmod{8}$ and is in fact equal to the image of $f$; i.e. comes from framed manifolds.

With this context in mind, roughly speaking, Adams showed that a nontrivial $\alpha$-invariant in dimensions $n \equiv 1, 2 \pmod{8}$ can always be realized by a stably framed closed manifold. Kervaire-Milnor showed that framed manifolds are always framed cobordant to a homotopy sphere in dimensions at least 5. Milnor may have separately shown that showed that the sequence of surgeries can be made to leave its $\alpha$-invariant unchanged, provided $n ≥ 9$ and $n \equiv 1, 2 \pmod{8}$. Surgery moves produce a cobordism and presumably, the sequence of surgeries produce a spin cobordism. Note that the result that $\alpha:\Theta_n \twoheadrightarrow \mathbb{Z}/2$ is surjective means the order of $\Theta_n$ is even for the $n$’s satisfying the conditions and that half of the exotic spheres cannot admit positive scalar curvature metrics because they have $\alpha \neq 0$. One can ask which of these homotopy spheres are those that bound parallelizable manifolds. A homotopy sphere bounding a parallelizable manifold means the homotopy sphere is also framed cobordant to the standard sphere. Since framings give rise to spin structures, the homotopy sphere would be spin cobordant to the standard sphere which has $\alpha = 0$ to due to its standard round metric of positive scalar curvature. So $\alpha(bP_{8k+i+1}) = {0}$ where $i=1,2$. However, this only shows $bP_{8k+i+1} \subset \ker \alpha$. For example, in dimension 9, the order of $\Theta_9$ is 8 and the order of $bP_{10}$ is 2. So there are 4 homotopy spheres with $\alpha = 0$, two of which bound parallelizable manifolds.

Let’s now state a refinement of the earlier Stolz’s theorem, still due to Stolz.

Theorem (Stolz): If $M$ is a simply-connected spin $n$-manifold of dimension at least 5, then $M$ admits a metric of positive scalar curvature if and only if $\alpha(M)=0$.

So if $M$ satisfies the conditions and is spin cobordant to a manifold with $\alpha=0$, then it must admit p.s.c. metrics. In fact, Stolz showed with stable homotopy theory that every simply-connected manifold of dimension at least 5 with $\alpha=0$ is spin cobordant to the total space of a fiber bundle with $\mathbb{HP}^2$ as fiber and structure group being the isometries of $\mathbb{HP}^2$ with the metric it inherits from $\mathbb{R}^{12} \cong \mathbb{H}^3$. One is always able to put a p.s.c. metric on such total spaces.

What are some other examples? If we take $V_d$ to be a degree $d$ smooth hypersurface in $\mathbb{CP}^{2k+1}$, then $V_d$ is spin if and only if $d$ is even; note that $\dim_\mathbb{R} V_d = 4k$. Also, $\widehat{A}(V_d) = \frac{1}{2^{2k}(2k+1)!} \prod^k_{j=-k}(d-2j)$ and so, if $d > 2k$ for all $k \geq 1$, then this is nonzero and so the $V_d$ cannot admit metrics of positive scalar curvature. For example, when $d=4, k=1$, we have a smooth quartic in $\mathbb{CP}^3$ which is better known as a K3 surface and $\widehat{A}(K3)=2$ (all K3 surfaces are diffeomorphic even though as complex surfaces, they have a large moduli space of complex dimension 20). However, being a K3 surface which is Calabi-Yau and hyperKähler, it admits a unique Ricci-flat metric which has scalar curvature exactly 0.

In dimension $n \equiv 1,2\pmod{8}$, the $\alpha$-invariant is $\mathbb{Z}/2$-valued and half of the exotic spheres in these dimensions have nonzero $\alpha$-invariant. As a result, if we have a compact spin manifold $M$ in one of these dimensions and $\Sigma$ is one of the exotic spheres with nonvanishing $\alpha$, then using connected sum, $\alpha(M \# \Sigma) = \alpha(M)+\alpha(\Sigma)$. So if $\alpha(M)=0$, we see that $M\# \Sigma$ cannot admit a metric of positive scalar curvature and moreover, $M\# \Sigma$ is homeomorphic though not diffeomorphic to $M$ since $M$ admits p.s.c. metrics. Thus:

Corollary: In dimensions $n \equiv 1,2 \pmod{8}$, every compact spin manifold is homeomorphic to a smooth manifold which cannot carry positive scalar curvature (possibly, itself) and also homeomorphic to a smooth manifold which does carry a positive scalar curvature metric (possibly itself).

Note: It is interesting to note that many of these theorems require that $n \geq 5$. When $n=4$, then the world of smooth topology is very wild and for any closed smooth 4-manifold, I believe that we either don’t know how many smooth structures it admits or we know there to be infinitely many. Now, the Seiberg-Witten invariant of a smooth 4-manifold $M$ and given $\text{Spin}^c$ structure is a useful tool for distinguishing diffeomorphism type. If a closed smooth manifold admits a positive scalar metric, then the Seiberg-Witten invariants all vanish; a theorem similar in form to Stolz’s theorem.

Appendix: more facts about $\Omega^{\text{Spin}}_*$ and the work of Adams

There is a forgetful map $f_*:\Omega^{\text{Spin}}_* \to \Omega^{SO}_*$ which has kernel being the ideal generated by the nontrivial spin structure on $S^1$ which generates $\Omega^{\text{Spin}}_1 =\mathbb{Z}/2$, call it $x$. Then, as said above, $\ker f_n = 0$ when $n \equiv 1,2 \pmod{8}$ and $\ker f_{8n+k}$, for $k=1,2$ is $U_{8n}\cdot x^k$ where $U_{8n} \subset \Omega^{\text{Spin}}_{8n}$ is a subgroup that maps isomorphically onto $\Omega^{\text{Spin}}_{8n}/\text{Tor}$. So the kernel in these cases is 2-torsion. Maybe in this case, $\alpha(x) = 1 \in KO_{8n+k} =\mathbb{Z}/2$.

Anyways, the spin cobordism ring can be thought of as coming from a $\mathbb{E}_\infty$ ring spectrum that is a Thom spectrum $M\text{Spin}$. Simarly, real K-theory is also a ring spectrum $KO$ and we have a map of ring spectra $\alpha:M\text{Spin} \to KO$. As a reminder, a ring spectrum $R$ has a unit map $\mathbb{S} \to R$ where $\mathbb{S}$ is the sphere spectrum which is associated with stable homotopy groups of spheres and also framed cobordism. Adams proved that the unit map is surjective in degrees $8n+1,8n+2$ and in fact, factors through $M\text{Spin}$: $\mathbb{S} \to M\text{Spin} \to KO$ where the first map is the unit map for the spin Thom spectrum and the second is the Atiyah-Bott-Shapiro orientation $\alpha$ which gives rise to the $\alpha$ we’ve been talking about on the level of graded rings. Simply by applying homotopy groups for spectra, we get $\Omega^{fr}_* \to \Omega^{\text{Spin}}_* \to KO^{-*}$. All that is needed to prove this surjectivity is that the $\alpha$-invariant of a point is 1; this is a statement about the homomorphism $\pi_0(M\text{Spin})\to \pi_0(KO)$.

Alternatively, let’s grant that we know there exists a homotopy sphere $\Sigma$ of dimension $8n+1$ with nontrivial $\alpha$-invariant. Then Milnor considered letting $M = \Sigma \times S^1$ where the circle has the nontrivial spin structure. So $\alpha(M) \neq 0$; if we surger $pt \times S^1$, we will then have a homotopy sphere with nontrivial $\alpha$-invariant of dimension $8n+2$.