A Counting Problem, Conjecture of Andrica and Tomescu, and the Lyapunov Central Limit Theorem

Published:

Recently, my friends and I were talking about the following problem. Let $n$ be a positive integer and consider sequences of $+$ and $-$ signs of length $n$. To each sequence, we can assign the $i$ th term to $i$ and hence, get a series which sums to some integer. For example, with $n=4$, the sequence $+,-,-,+$ gives $1-2-3+4 =0$. In fact, for any consecutive 4 integers, this sequence gives 0: $k-(k+1)-(k+2)+(k+3)=0$.

Question: For a given $n$, how many sequences are there that sum to $0$?

Note that modulo 2, the series always sum to something congruent to $n(n+1)/2 \pmod{2}$. It’s also easy to show that for $n\equiv 1,2 \pmod{4}$, the series always have odd sums and hence, cannot sum to 0. For $n \equiv 0,3 \pmod{4}$, there exist such sequences. Using the above, we see that if $n=4k$, then since every consecutive 4 integers can be assigned $\pm$ so that those 4 sum to 0, we get a sequence.

We can do somewhat better by taking a hint from 10-year old Gauss. Write out $1,…,2k$ in ascending order and beneath it, right $4k,…,2k+1$ in descending order. Each column has two entries that sum to $4k+1$ and there are $2k$ entries. So we just need to assign $+$ to $k$ of these columns and $-$ signs to the rest; this gives us ${2k \choose k}$ sequences which is our lower bound.

For $n=4k+3$, we can do a similar thing but we’ll write out $1,…,2k$ in ascending order and beneath it $4k+2,…,2k+3$ in descending order. We leave $2k+1,2k+2,4k+3$ aside. Then these columns all add up to $4k+3$ and there are $2k$ of them. Like above, we can assign $\pm$ to get a sum to 0. Lastly, we can assign $+,+,-$ or $-,-,+$ to the three we put aside; these two assignments also give sums of 0 for the three. So we have a lower bound of $2{2k \choose k}$ for $n=4k+3$. Let’s summarize what we know so far:

Proposition: For a given positive integer $n$, there exists a sequence of $+,-$ so that the associated sequence sums to 0 if and only if $n \equiv 0,3 \pmod{4}$.

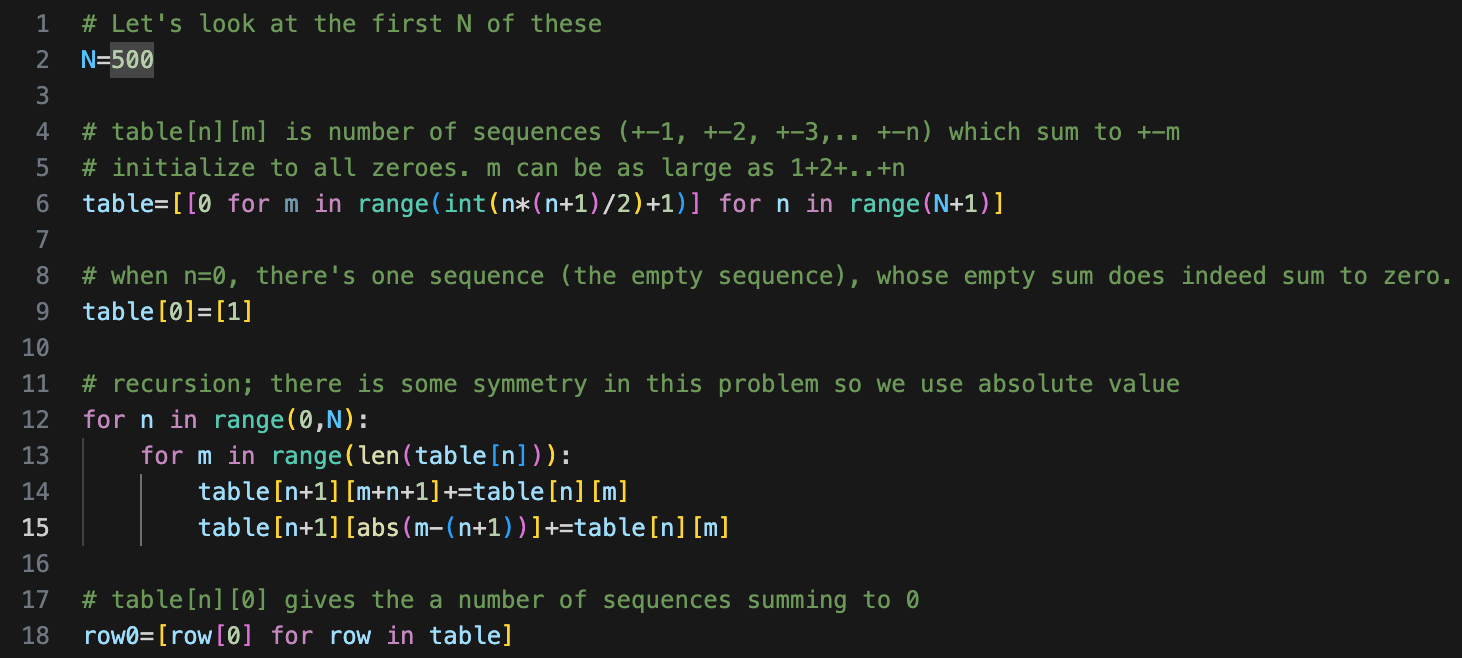

Let’s work a bit more generally. For a given $n \in \mathbb{N}$ and $m \in \mathbb{Z}$, we can count sequences for $n$ that sum to $m$. Let’s call the count $Q(n,m)$. Note that we can recursively calculate this: $Q(n,m)=Q(n-1,m-(n-1)) + Q(n-1,m+(n-1))$. Here is some code which runs this recursive definition (with caching), courtesy of one of my friends.

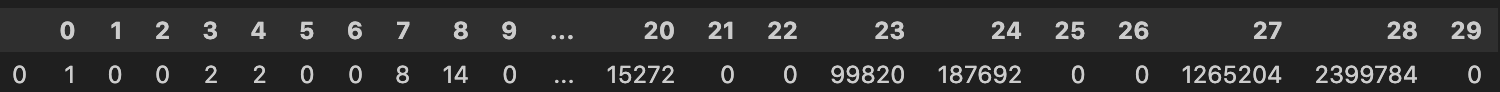

Here are the counts for up to $n=29$.

The counts increase rather quickly! This sequence is stored on the OEIS.

Asymptotic Behavior

Now, let’s see if we can detect any asymptotic behavior. We’ll try a probabilistic approach. If we assign each number in $1,…,n$ to be randomly positive or negative with 50/50 probability, what is the probability that the sum $S(n)$ is zero? Again more generally, let $q_n(m)$ be the probability that the sum is $m$. This is equal to the number of $m$-sum sequences divided by the total number of sequences: $Q(n,m)/2^n$. So if we know the probability, we can multiply by $2^n$ to get the number of sequences with $m$.

Now since the sign of each term is randomly chosen, independently of the other terms, we can represent each coordinate as an independent random variable. Let $X_k$ be the variable for the $k$ th term. It is either $-k$ or $k$ with equal probability and the sum $S(n)=\sum_{k=1}^n X_k$ is a sum of independent variables, with discrete probability distribution $q_n(m)$. These are not identical variables but the Lyapunov Central Limit Theorem roughly says that as long as we have finite means and the finite variances of these variables are not too far apart, the sum still converges to a normal distribution.

To be more precise, Suppose $X_1,…,X_n$ is a sequence of independent random variables, each with finite expected value $\mu_k$ and variance $\sigma^2_k$. Define $s^2_n$ to be the sum of the variances. If for some $\delta >0$,

$\lim_{n\to \infty }\dfrac{1}{s_{n}^{2+\delta}} \sum_{i=1}^n \mathbb{E} \left[\left|X_k-\mu_k\right|^{2+\delta}\right]=0$

is satisfied (Lyapunov condition), then the $\dfrac{1}{s_n}\sum^n_{k=1}(X_k-\mu_k)$ converges in distribution to a standard normal random variable $N(0,1)$.

For us, each $\mu_k = 0$ and $s^2_n = \sum^n_{k=1} k^2 = n(n+1)(2n+1)/6$. If we let $\delta=1$, then the expected value sum in the Lyapunov condition is simply $\sum^n_{k=1} k^3 = n^2(n+1)^2/4$. In other words, we have the interesting fact that $1^3+2^3+…+n^3=(1+2+…+n)^2$. This is $O(n^4)$ but $s^3_n$ is of order $O(n^{4.5})$. So the limit is indeed 0 and Lyapunov’s condition is satisfied.

Thus, the result is that for large $n$, $q_n(m)$ converges to a normal distribution with mean $\mu=0$ and variance $s^2_n = n(n+1)(2n+1)/6$ in distribution.

We need to recall that convergence in distribution is a rather weak form of convergence and this is both a feature and a bug. If I have random variables $X_1,…,X_k,…$ which don’t even have to be defined on the same sample space, I can consider their probability cumulative distribution $F_k(x) := P(X_k \leq x)$. If I want to know the probability of $X_k$ being between $a$ and $b$ where $a<b$, I just need $F_k(b)-F_k(a)$. This is a real valued function $F_k:\mathbb{R} \to [0,1]$ and is always defined even if the random variable is neither discrete nor continuous. But if there exists a probability density function $f_k$ such that $F_k(x) = \int^x_{-\infty} f_k(t)\,dt$, then we say that $X_k$ is a continuous random variable.

Let’s also observe that for a discrete variable, we can embed its values into the reals so that its PCD is a step function and we can define Dirac delta “functions” to be the density for these. So in this sense, discrete random variables can be included in the continuous case. Let’s also consider a random variable $X$ with PCD $F$. Then, $X_k \to X$ in distribution means that $F_k(x) \to F(x)$ for every $x$ at which $F$ is continuous.

We can see that for us, we really do need this weaker notion of convergence since we’re talking about discrete random variables converging to a continuous random variable. Moreover, $q_n(m)$ is zero for every other term because when $m\neq \sum_{k=1}^n k \pmod{2}$, then there are no such sequences of $+,-$.

So how can we approximate the specific value of $q_n(0)$, our actual goal? Here is a wild assumption: Let $f$ be the probability density function of the normal distribution of interest; i.e. the one with $\mu=0$ and variance $s^2_n = n(n+1)(2n+1)/6 \approx n^3/3$ and assume $q_n(m)\approx 2 f(m)$. We choose this scaling factor of 2 to account for the fact that the probabilistic mass is squeezed into only half of the available terms. In other words, we’re approximating $q_n(m)$ by integrating $f$ over an interval of width 2. Since the variance is so large, then $f$ is very flat and so the integral of $f$ from $-1$ to $1$ is approximated by a rectangle of width 2 and height $f(0)$.

So conditional on this wild assumption, we calculate $q_n(0)=2f(0)=\frac{2}{\sqrt{2\pi n^3/3}} e^0 = \sqrt{\frac{6}{\pi n^3}}$. Finally, we multiply by $2^n$ to obtain the count: $Q(n,0) \approx 2^n \sqrt{\frac{6}{\pi n^3}}$ for very large $n \equiv 0,3 \pmod{4}$.

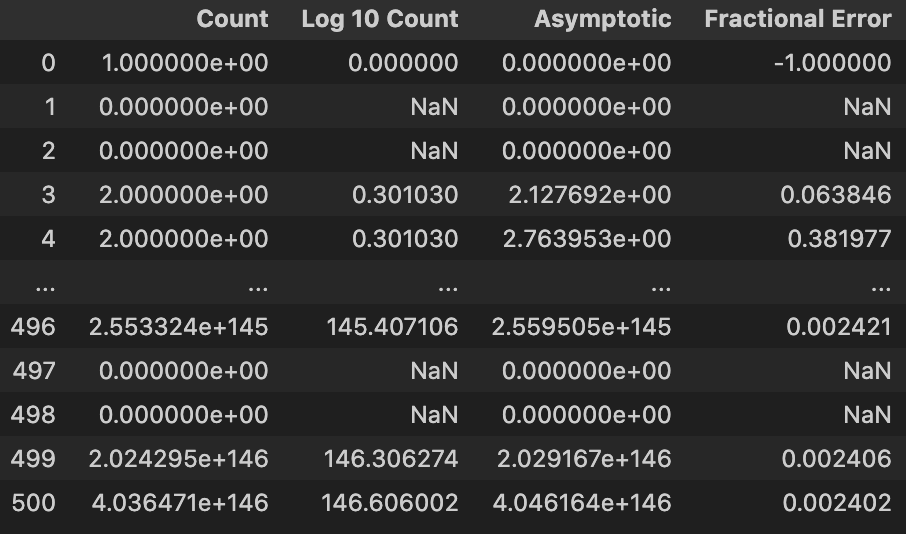

Here is a table (up to $n=500$) to show the actual counts compared to the asymptotics and also some error.

Another attempt to try and justify the wild assumption goes as follows: The discrete random variable $q_n(m)$ (which is a sum of Bernoulli random variables) only takes on integer values and so if we want to find $q_n(0)$, we can look at the cumulative distribution $P(q_n <1) - P(q_n \leq -1)$. The probability should all be concentrated at 0. One issue, however, is that we could replace $1$ with any positive value $a<1$ and should still get the same answer but the integral of $f$ on $[-a,a]$ will be different.

As it turns out, it was a conjecture of Andrica and Tomescu (2002) that for $n \equiv 0,3 \pmod{4}$, as $n \to \infty$, the counts approach $2^n \sqrt{6/\pi n^3}$. This was proven by B. D. Sullivan (2013) in her paper using non-probabilistic methods. I imagine that our probabalistic sketch (with the wild assumption) would need a fair amount of reworking if it’s to be valid. Even so, I still hope for some kind of probabilistic proof of this asymptotic result.

Bonus Application of the Central Limit Theorem

Claim: $e^{-n}(1+n+n^2/2!+n^3/3!+…+n^n/n!) \to \dfrac{1}{2}$ as $n \to \infty$.

Let $X_1,…,X_n$ be independent and identically distributed discrete Poisson random variables with mean equal to 1 (and hence, also variance equal to 1). Let’s use a probability generating functions because the Poisson random variables are all discrete and take values in nonnegative integers. As a reminder, $G_X(s) = E[s^X] = \sum^\infty_{k=0}P(X=k)s^k$ and it completely determines $X$ (when $X$ is a nonnegative integer valued random variable). Moreover, $G_{X+Y}=G_X G_Y$ when $X,Y$ are independent.

So for a Poisson variable, $P(X=k) = \lambda^k e^{-\lambda}/k!$ and the mean and variance are both $\lambda$. For this problem, we set $\lambda = 1$. Thus, $G_X(s) = e^{-1}\sum^\infty_{k=0}\dfrac{s^k}{k!} = e^{s-1}$. Then $G_{S_n}(s) = e^{n(s-1)}$ because of independence. One useful thing about any PGF for such random variables is that differentiation gives us moments; e.g. $G’_X(1)=E[X]$. That is, the 1st derivative evaluated at $s=1$ gives the expected value since $G_X(s) = E[Xs^{X-1}]$. Remember, $X$ is integer valued and though we call it a random variable, for fixed occurrences, we should view it as an unchanging power. So we can use the power rule rather than treat it as an exponential. Anyways, $G’_{S_n}(1)=n$.

Now, the Central Limit Theorem tells us that the sum of $n$ i.i.d random variables $X$ with mean $\mu$ and finite variance $\sigma^2$ (call this sum $S_n$), has the following behavior: $\dfrac{S_n -n\mu}{\sigma\sqrt{n}} \to N(0,1)$ in distribution. So this tells us that the $S_n$ concentrates at $n\mu$ with fluctuations on the order of $\sqrt{n}$. In our situation, $\mu = \sigma^2 = 1$ so we have $\dfrac{S_n -n}{\sqrt{n}} \to N(0,1)$ in distribution.

On the other hand, the expression we’re given is $P(S_n \leq n) = e^{-n}(1+n+n^2/2!+n^3/3!+…+n^n/n!)$ which we can find by truncating the power series $G_{S_n}(s)$ at the $n$ th term, then plugging in $s=1$. By the Central Limit Theorem, for very large $n$, $P(S_n \leq n) = P(S_n-n \leq 0) = P\left(\dfrac{S_n - n}{\sqrt{n}}\leq 0\right) \approx P(Z\leq 0) = \dfrac{1}{2}$. The 2nd equality is just from the fact that $0\cdot \sqrt{n}=0$ still. The $P(Z\leq0)$ is where $Z \sim N(0,1)$.