An Application of Topology to Gravitational Lensing

Published:

Here is an interesting application of topology that I learned from Cumran Vafa. In astronomy, there is the phenenomenon of gravitational lensing which is when light shining from some star or galaxy gets bent as it travels towards us on earth. The bending is due to a strongly gravitating object such as a black hole (the light doesn’t “fall in” if it doesn’t cross the event horizon). Thus, we sometimes see multiple images of the same object because of this effect. We may even see the images inverted, similar to how when you look at your own reflection in a spoon, depending on the distance you hold it from yourself, you might see your image flipped. Here is an image, courtesy of NASA. Note that around the center, we have four bright white spots which look similar. I believe these should actually all be the same object, just seen more than once due to this effect.

Here is the application of topology:

Proposition: Let $n$ be the number of normal images we see of a light source due to the effect of some gravitating object and $i$ be the number of inverted images we see of the same light source due to the same gravitating object. Then $n-i = +1$; i.e. there is always one more normal image than inverted image. Also, the total number of images $n+i$ is an positive odd integer.

Remark: When looking at some images, we might count an even number of total images. This may be because our telescope isn’t able to pick up on some of the images due to other effects. Or, it may be due to having multiple gravitating objects. The proposition is still applicable; just apply it to each gravitating object, one at a time. So, assuming that there’s nothing obscuring any of the images, if we count an even number of total images, we can be sure there is more than one strongly gravitating object. In other words, this proposition serves as a “detection device” for strongly gravitating objects.

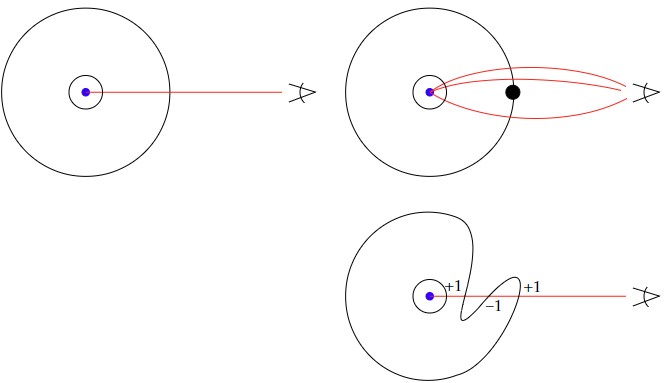

Proof: Let’s consider the pictures below to guide our thinking. We have a blue object giving off light and if there is no gravitating object around it, then the light it gives off forms an expanding sphere or bubble of light, an $S^2$. In the picture below, I’ve drawn circles instead. We can form a map from the larger sphere to a tiny sphere around the blue object just by tracing the path of light (one light ray is shown in red); it will be a continuous homeomorphism and will have degree $+1$; i.e. it has the homotopy class of $+1 \in \pi_2(S^2) \cong \mathbb{Z}$ which is the same class as the identity map. The light ray makes it’s way to the observer. I’ll give a simpler definition in a moment.

Now, if there is a gravitating object (shown as a large black dot), we can imagine that we may “turn off” its gravitational effect so that we start out in the first picture, then slowly turn gravity back on to its full strength. We can think of this as distorting the path of different light rays so that they end up at the same place (see the top right picture). Alternatively, we can think of it as a continuous distortion of the bubble of light, as shown in the bottom picture. Essentially, we take the three red rays and collapse them to a single straight light ray but must do so in a way to “drag” the bubble of light along with them. This gives a deformed sphere and we may count how many times the now straight ray passes through the deformed sphere. So in the picture, the three points that the red ray passes through are each mapped to the same point on the tiny sphere.

Since we have a continuous deformation, the degree of the new map is still $+1$. However, to make sense of this, we can make use of an alternative but simpler (conceptually speaking) definition of the degree of a differentiable map $f:S^2 \to S^2$. Take a generic point $p \in S^2$ in the target and count its preimage points $x \in f^{-1}(p)$, up to sign. The generic point has finitely many preimage points and the way to associate a sign is to see if locally orientation preserving or reversing at each $x$. One way to determine this is think of $S^2 \subset \mathbb{R}^3$ and compute the linearization of $f$ at $x$; this is a $3 \times 3$ matrix and if its determinant is positive, it is orientation preserving there. If negative, it is orientation reversing.

So in our picture, we need to assign to each of the 3 points, $+1$ or $-1$, depending on the orientation. The $-1$ corresponds to inverted images and we see that in total, it must be that $n-i =+1$. Of course, $n-i + 2i$ is an odd number plus an even number and hence, is odd. The gist of this argument works also in other situations than when there are only 3 points. $\square$

Remark: The reader may note that there’s an issue if the light ray lies tangent to the sphere in the picture. However, such occurences have measure 0 and so, what this means in practice is to just move a bit, as an observer. Since the earth and satellites rotate and are in orbit, these situations can be easily avoided.