An Application of Topology to Primitive DNA Replication

Published:

This is another post where I give an application of topology to something outside of math. In my freshmen year of college, some friends and I were too tired to do homework after dinner but too awake to go to bed. So we began cutting up strips of paper and then taping them to gether with various twists and seeing what would happen when we cut these up again. The most well-known of these creations is a cylinder where you simply take a long rectangular strip of paper and tape the two ends together without any flourish. But the second-most well known is the Möbius band which is made from taking a long rectangular strip of paper, making half a twist in the strip, and then taping the two ends together. If you then cut the cylinder by following the midline of the strip, you’ll get an unsurprising result: you cut it into two cylinders. However, what happens if you cut the Möbius band in a similar way down the midline? If you’ve never done this before and want to give it a try, pause here and don’t read on. I’ll put a picture of the Lofoten Islands in Norway here for you to enjoy while you do some “experimental mathematics.”

If you did things correctly, you should have found that the Möbius band, when cut that way, does not give you two pieces but one! Moreover, somehow, there are many twists in it. If you count carefully, you’ll find four half-twists. There is a Numberphile video featuring Tadashi Tokieda who demonstrates some of these and gives an explanation for what’s going on. There’s also a follow-up video where he continues the exploration.

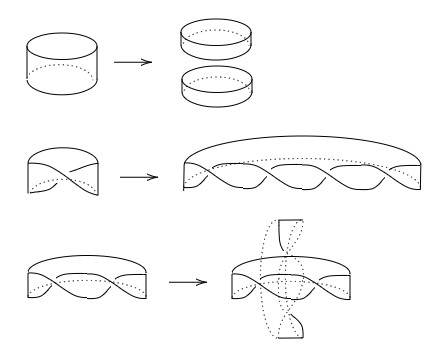

What if you take the result of cutting the Möbius down the midline and do a second cut down the midline of the new band? You can give this a try yourself but what you’ll find is that it will be cut into two pieces but now there’s another surprise: the two pieces are interlinked! In general, if you make $n$ twists, you’ll get only one piece if $n$ is odd and get two pieces if $n$ is even. If $n$ is even and at least 2, then the two pieces will be interlinked. Here is a picture to illustrate a few examples with 0, 1, and 2 twists. The picture gets a bit messy but you can always try it yourself with paper, scissors, and tape!

On a related note, we can think of these bands as real line bundles over the circle $S^1$ and the number of twists $n$, reduced mod 2, is known as the 1st Stiefel-Whitney class $w_1(L)$ of the line bundle $L \to S^1$. This is in fact a complete invariant of real line bundles over $S^1$ and can take on values either 0 or 1 (whether $n$ is even or odd). Being a complete invariant means that if two such line bundles have the same $w_1$, then they are isomorphic. Also, if $n$ is odd (so $w_1 = 1$), then $L$ is nonorientable. You can check this with the Möbius band; if you draw a line along the band without lifting your pen, you need to circle around twice before you get back to where you started. But now, if you go around only once but keep track of an upwards directing as you go along, you’ll find that the direction will flip and be pointing down when you make it to your starting point after one loop. This proves the nonorientability.

Application to DNA Replication in Primitive Bacteria

I learned this idea from a biologist at CUNY who spoke at Jim Simons’ 85th birthday math/physics celebration. Unfortunately, I have forgotten his name so if anyone was there at CUNY and could let me know who this man is, I’ll be very grateful.

Anyways, primitive (early) bacteria have DNA strands that form loops rather than strands. This is because it’s easier, instruction wise, to not have to deal with ends. If you have ends, you need to distinguish points on the interior and points on the boundary. If you’re a protein with some instructions for interacting with the bacteria, it becomes more complicated to have to deal with these. So one can imagine that simpler lifeforms would have DNA loops.

Next, for biochemical reasons (according to the biologist), the DNA is twisted with an even number of half-twists. This means that it is orientable and so when cut down the middle, it will separate into two halves. Let $n$ be the number of half-twists. So $n \equiv 0\pmod{2}$. If $n=0$, then the two halves separate. But if $n \geq 2$ and even, the two halves are interlinked.

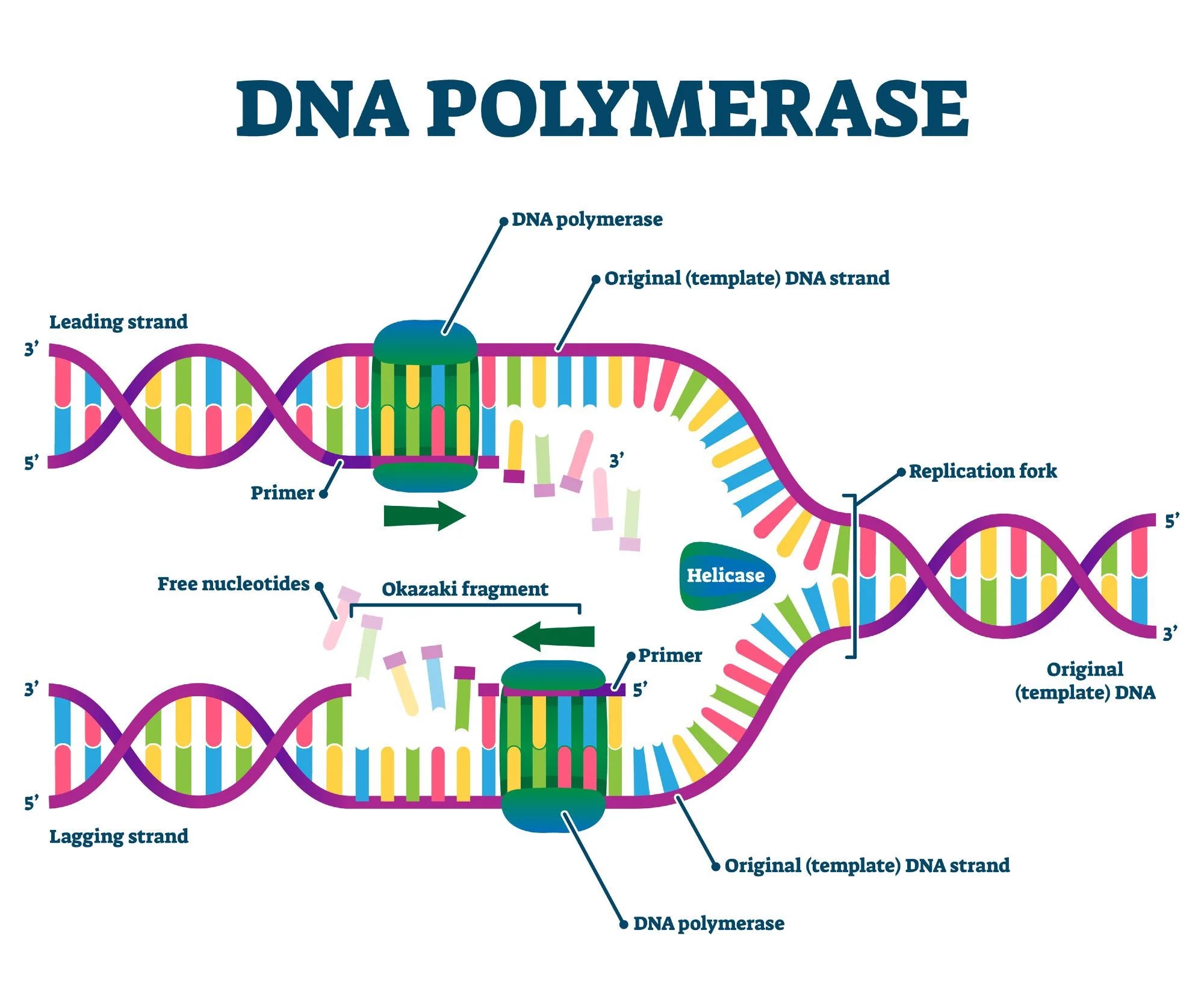

So when does DNA get cut down the middle? During DNA replication, (which also occurs in plants and animals), the strand is essentially cut in half (or unzipped) by an enzyme called a helicase. Then, each half is replicated and new strands are formed by the DNA polymerase. The fact that you have this interlinking of the new “half” strands means that the DNA pices don’t float away. Then the DNA polymerase can perform replication more easily without having to search far and wide for the different pieces. From an evolutionary biology perspective, this increases the chances for life to form since keeping the strands nearby is very helpful.

Thus, if you like, a study of the topology of these paper strips leads us to some insight into some of the mechanisms for increasing the probability of successful DNA replication!