The Circular Restricted Three Body Problem and the Poincaré-Birkhoff Theorem

Published:

In October 2023 ago, I wrote a post about the Three Body Problem and how it’s an example of a chaotic system and moreover, is not completely integrable. Recently, I’ve been reading Agustin Moreno’s wonderful lecture notes on the subject, particularly because his aim is to show how symplectic and contact topology apply to the study of the Three Body Problem. I wanted to write down some of what I learned; nothing here is original to me. In particular, I want to write about the Circular Restricted Three Body Problem (CR3BP). This is a version of the traditional problem where three point masses live in a system where only Newtonian gravity is at play. One of the masses is assumed to be much smaller than the others so that it is essentially negligible; i.e. it’s movement is influenced by the two primary masses but it does not affect the movement of the primaries. Moreover, it is assumed that the other two masses move in circles around their common center of mass.

Let’s just take the earth and moon as an example. We have the mass ratio $\mu = m_M/(m_M + m_E)$. We can find a suitable inertial plane in which the earth and moon move so that the position of the earth is $E(t)= (\mu \cos t,\mu \sin t,0)$ and the moon’s position is $M(t) = (-(1-\mu)\cos t, -(1-\mu)\sin t,0)$.

The Hamiltonian we would want to study is then the kinetic energy plus the two gravity potentials but note that it is time-dependent. To remedy the time-dependence, we may choose rotating coordinates which puts the primaries at rest but the cost is to introduce centrifugal and Coriolis effects. The way to do this is simply to introduce a term which adds a rotation of the plane to the Hamiltonian. The term $p_1q_2-p_2q_1$ does the trick. Hence, the following Hamiltonian is now autonomous:

\(H: \mathbb{R}^3 \setminus \{E, M\} \times \mathbb{R}^3 \to \mathbb{R},\) \(H(q,p) = \frac{1}{2}\|p\|^2 − \frac{\mu}{\|q -M\|} -\frac{\mu}{\|q -E\|} + p_1q_2 - p_2q_1\)

We may restrict our attention to when $q_3=p_3=0$ in order to study the planar problem; the flow preserves this subset. We also have two antisymplectic involutions: \(\rho(q_1,q_2,q_3,p_1,p_2,p_3)=(q_1,-q_2,q_3,-p_1,p_2,-p_3)\) \(\bar{\rho}(q_1,q_2,q_3,p_1,p_2,p_3)=(q_1,-q_2,-q_3,-p_1,p_2,p_3)\)

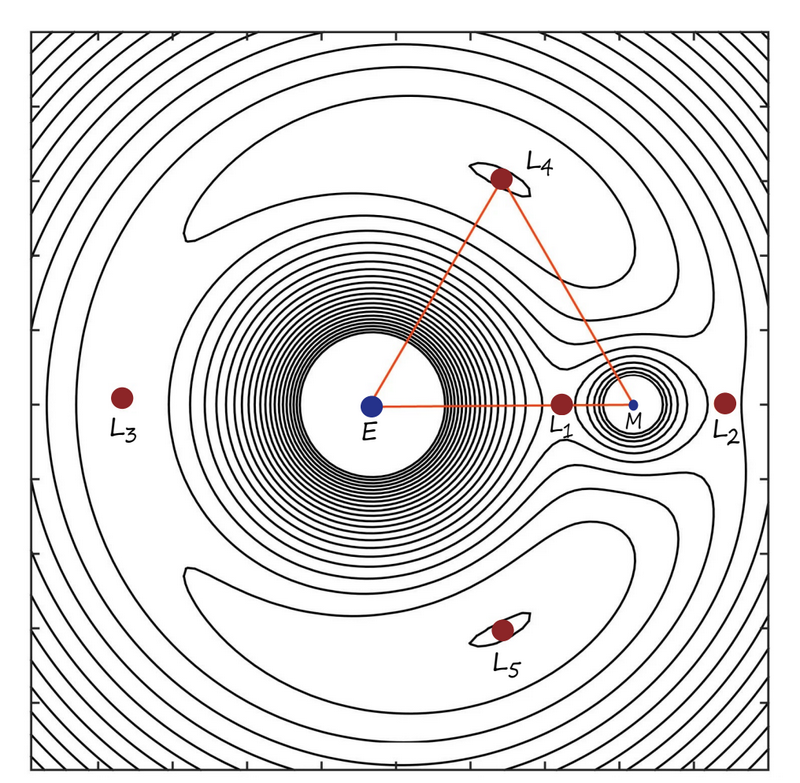

The fixed points of these involutions are Lagrangians. Also, note that $\sigma = \rho \circ \bar{\rho}$ is a symplectic involution which adds minus signs to $q_3$ and $p_3$. So the fixed point locus of $\sigma$ is where the planar problem resides. One can, in the footsteps of Euler and Lagrange, find that this Hamiltonian has 5 fixed points which are called Lagrange points.

The points in the diagram (from Moreno’s notes) are labeled so that their energy is in increasing order when the mass ratio $\mu < 1/2$; i.e. $H(L_1) < H(L_2) < H(L_3) < H(L_4) < H(L_5)$. When $\mu=1/2$, we have that $H(L_2)=H(L_3)$. $L_1,L_2,L_3$ are saddle points while $L_4,L_5$ are local maxima. In the plane, these two actually form equilateral triangles with $E$ and $M$ as the other vertices! The curves represent level sets of $H$ which visually depict $L_1,L_2,L_3$ as saddle points.

There are many Lagrange points in our solar system. For example, we have 5 Lagrange points associated to the system where the earth and sun are primaries. Since they are stable points, we’ve put objects at those points. For example, at $L_1$, the Deep Space Climate Observatory (DSCOVR) is studying solar wind. At $L_2$, the James Webb Space Telescope is taking pictures of faraway objects to understand the cosmological past. Both of these points sit about 930,000 miles from earth which is quite far but still only about 1% the distance to the sun. Jupiter and Saturn also have such Lagrange points as do the earth and moon. Moving forward, let’s just use the earth and moon as examples.

Now, we note that there is noncompactness for the 5-dim level sets of $H$. For instance, when $q = E$ or $q=M$ corresponds to the sattelite crashing into the earth or moon and the potential energy diverges. One way to deal with this is to compactify our position space and work with a new Hamiltonian $Q:T^*S^3 \to \mathbb{R}$ which agrees with the original Hamiltonian away from the newly added points. Roughly speaking, the way to arrive at $T^*S^3$ is to do a trick due to Moser of interchanging $p$ and $q$. Then where $p=\infty$ which represents collision, we do a real oriented blow-up to add in all the directions in which the collision can occur; i.e. add in a copy of $S^2$. Moreover, the energy hypersurface (level set of $Q$) can be described topologically. For $c \in \mathbb{R}$, consider $\Sigma_c = H^{-1}(c)$. For details, see Moreno’s notes.

If $\pi: \mathbb{R}^3 \setminus \{E, M\} \times \mathbb{R}^3 \to \mathbb{R}^3 \setminus \{E, M\}$, $\pi(q, p) = q$ is projection onto the position coordinate, we define the Hill’s region of energy $c$ as $K_c = \pi(\Sigma_c)$. This is the region in space where the satellite with energy $c$ is allowed to move. If $c < H(L_1)$ lies below the first critical energy value, then $K_c$ has three connected components: a bounded one around the Earth, another bounded one around the Moon, and an unbounded one. Namely, if the satellite starts near one of the primaries, and has low energy, then it stays near the primary also in the future; e.g. it lacks the energy to travel from the earth to the moon. The unbounded region corresponds to asteroids which stay away from the primaries. Denote the first two components by $K^E_c$ and $K^M_c$ and $\Sigma^E_c = \pi^{-1}(K^E_c) \cap \Sigma_c$ and similarly for $\Sigma^M_c = \pi^{-1}(K^M_c) \cap \Sigma_c$.

When $c$ crosses the 1st critical value $H(L_1)$, then $\Sigma^E_c$ and $\Sigma^M_c$ get surgered together by connected sum and we get a new hypersurface $\Sigma^{E,M}_c$. We may compactify these in $T^*S^3$ to get $\overline{\Sigma}^E_c$ and $\overline{\Sigma}^M_c$. Let $S^*S^3 = S^2 \times S^3$ be the sphere bundle. Then $\overline{\Sigma}^E_c$ is a connected sum of two copies of $S^*S^3$. If you’re familiar with Morse theory, you’ll recognize that this surgery should take place since $L_1$ is a saddle point for $Q$. The interpretation is that the satellite now has enough energy to move around between the regions near to earth and the moon.

In the planar problem, the situation is similar: we compactify $\mathbb{R}^2$ to $S^2$ and obtain copies of the circle bundle $S^*S^2 = \mathbb{RP}^3$ as energy hypersurfaces. There is a way to study these by using the double cover $S^3 \to \mathbb{RP}^3$. Of course, these energy hypersurfaces are contact manifolds where the contact form comes from the exact symplectic form on $T^*S^3$ or $T^*S^2$.

The Planar Problem for CR3BP and the Shape Sphere

Let’s restrict ourselves to the planar problem and make the simplifying assumption that they all have the same mass. Let $x_1,x_2,x_3$ denote the coordinates of the three bodies; we’ll think of these living in $\mathbb{R}^2 \subset \mathbb{R}^3$. Let $v=x_2-x_1,w=x_3-x_1$. Then consider the following new coordinates: $(v\cdot w,v^2-w^2,(v\times w)\cdot e_z)$.

Here, we use the dot product and cross product. So $v^2=v\cdot v$, for example. Note that $v\times w$ is already parallel to the $z$-axis so the dot product with the unit vector $e_z=(0,0,1)$ is just to get the $z$-component. The only way for $(v\times w)\cdot e_z = 0$ is for $v$ and $w$ to be parallel which means that $x_1,x_2,x_3$ are collinear. Also, note that when $x_1=x_2$, then $v=0$ in which case we’d have coordinates $(0,-w^2,0)$; the $y$-value is nonpositive. When $x_1=x_3$, then $w=0$ and the coordinates are $(0,v^2,0)$; the $y$-value is nonnegative. When $x_2=x_3$, then $v=w$ and so the coordinates are $(v^2,0,0)$.

The only way for all three coordinates to be $0$ are if $x_1=x_2=x_3$ where the three bodies have all collided. Supposing this doesn’t happen, we can normalize the vectors to unit length so that we’re looking at the unit sphere, also called the shape sphere. For the sake of legibility, I won’t change our notation to reflect this move to the sphere. Note that the first coordinate being $v\cdot w = |v||w|\cos \theta$ where $\theta$ is the angle between $v$ and $w$.

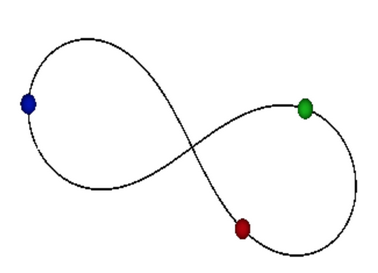

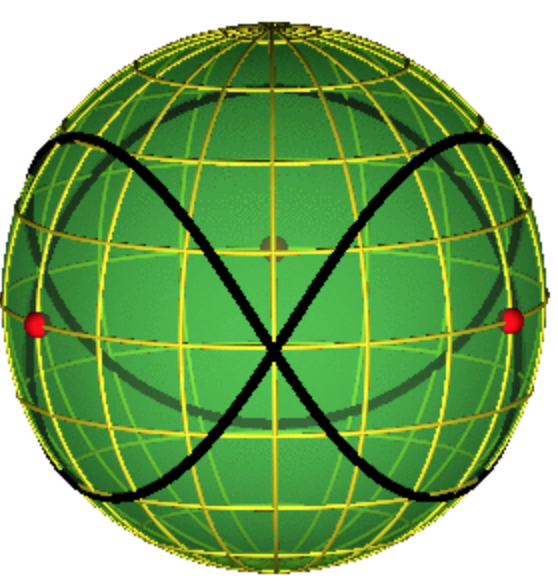

The points $(1,0,0),(0,1,0),(0,-1,0)$ correspond to when 2 of the 3 bodies have collided. So a stable periodic solution to the planar 3 body problem gives rise to a loop on the shape sphere that avoids these three points. Since $S^2 \setminus 3\text{ pts} \cong \mathbb{R}^2 \setminus 2 \text{ pts}$ and the fundamental group is the free group $\mathbb{Z}* \mathbb{Z}$, we can describe the loop by its homotopy type. Call the generators $a,b$ and for ease, let $A=a^{-1},B=b^{-1}$. For example, there is a solution called the Figure 8 whose homotopy class is described by $abAB$; the figures below show the orbit and the shape sphere. It is (one of?) the only known stable solutions. There are other known solutions but they are very sensitive to their initial conditions and can also be quite complicated. For example, the one called Moth III has homotopy class $AbabABAbabABabaBABabaB$. See here for more orbits; click the link to the gallery to see some shape spheres. Note they use somewhat different coordinates.

Now, the three bodies can be viewed as being vertices of a triangle and by conservation of momentum, their center of mass is always fixed. Above, our coordinates, in a way, track something about the angles of the triangle though maybe this is only apparent in the first coordinate $v\cdot w$. Note we only need 2 of the 3 angles since the 3rd is determined by the first two. With this in mind, it’s maybe easier to see that we may form a shape sphere for situations when the masses differ and also when the orbits are not planar. The shape sphere can still track the two angles of the triangle and so, we may think of the sphere as a moduli space of triangles up to similarity, translation, and rotation. That is, we don’t care about the size of the triangle, only their relative lengths or equivalently, angles. And we also don’t track the orientation of the triangle in space though we do care about its internal orientation. Namely, when crossing the equator, the orientation flips. Though there is some loss of information, the shape sphere can still be fruitful to study.

Also, recall that there is a Hopf fibration $S^3 \to S^2$. The preimage of a point is a circle. I’m not sure how to interpret this circle if we think of the point as describing a triangle up to similarity and rotations; perhaps the circle corresponds to the triangle rotating in the plane it’s contained in. For example, the $L_4$ and $L_5$ Lagrange points are where the three bodies form an equilateral triangle while the other three are when they are collinear. So on the shape sphere, the orbits associated to $L_1,L_2,L_3$ are on the equator and the orbits associated to $L_4,L_5$ should give $(\frac{1}{2},0,\pm\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2})$.

Surface of Section and Annulus

G. W. Hill found, when studying the movement of the moon, that there is a direct orbit for the moon: an orbit where the moon rotates in the same direction around the Earth as the Earth around the Sun. There is also the opposite situation: a retrograde orbit where the moon rotates in the opposite direction. This made a large impression on Poincaré who then earnestly studied the system using these two orbits. To understand how, let’s introduce some definintions for the context of the planar CR3BP.

Definition: A surface of section $S \subset (Y^3,\alpha)$ in a contact 3-manifold is a surface with boundary being finitely many Reeb orbits, the Reeb trajectories intersect the interior of $S$ transversally in the past and the future (so at least twice).

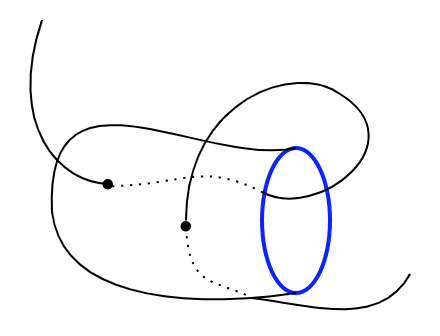

Here is a picture of a (topological) disk as a surface of section (these are also called Poincaré sections). I’ve drawn an orbit which intersects the disk transversally in two points.

The main point here is that we had a continuous dynamical system but for certain purposes, we can reduce our study of it to looking at a discrete problem. For example, if we want know what the long term behavior of the system is, particular if there is stable behavior, we can study the 1st return map, also called the Poincaré return map and see where a point in the surface of section goes under many iterates; this can often be done numerically; there is a nice Python module called Rebound for studying $n$-bodies under the effects of gravity. This makes sense since the trajectories intersect at least once in the past and once in the future. Also, surfaces of section have a symplectic structure and this map is a Hamiltonian diffeomorphism on that surface.

Going back to the direct and retrograde orbits of the moon, we may use the double cover $S^3 \to \mathbb{RP}^3$ and lift these two orbits to a pair of unknots in $S^3$. However, they are linked to each other; i.e. we have the Hopf link which bounds an annulus $A$. This annulus projects back down to a surface of section. By Stokes Theorem, the symplectic area of the annulus measures the difference in the action of the two orbits (or rather, maybe twice the difference since we used the double cover).

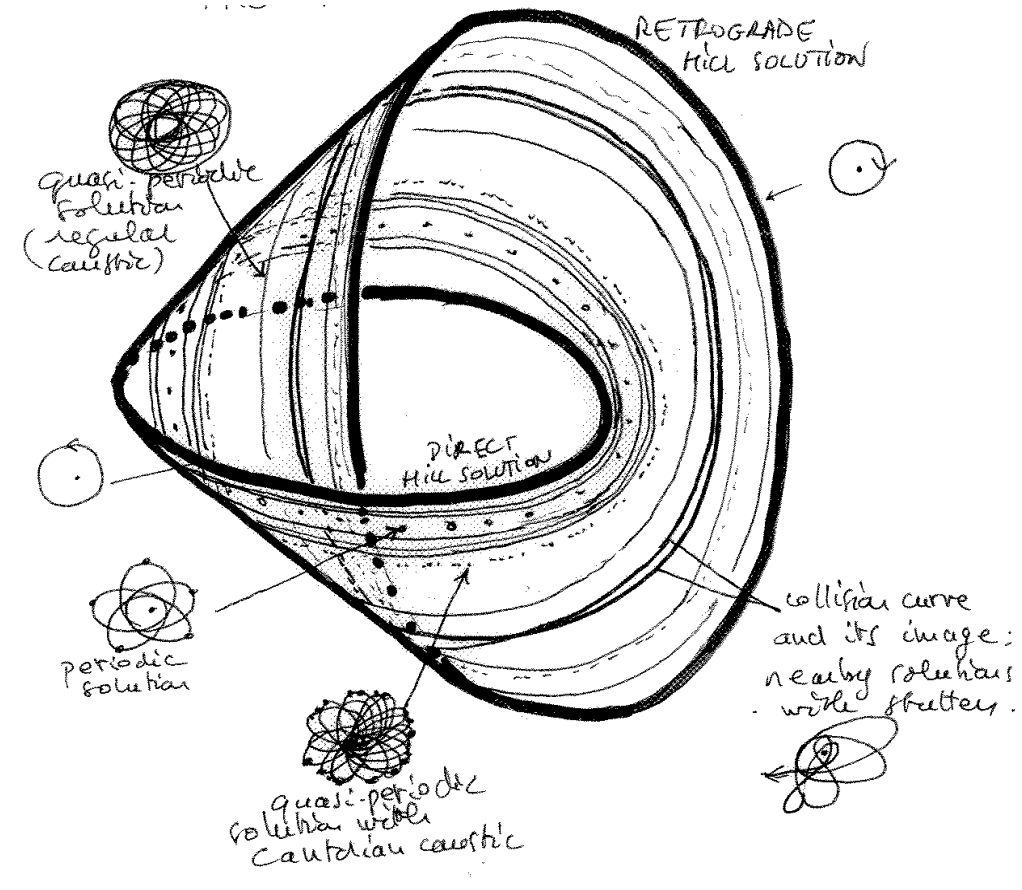

This picture is from Alain Chenciner’s article, p. 59.

This picture is from Alain Chenciner’s article, p. 59.

Since the direction of orbit of the direct and retrograde orbits are opposite to each other, the Poincaré return map is an area preserving map of the annlus $A$ which twists; i.e. it rotates the boundary components in opposite directions. Enter now the famous theorem studied by Poincaré in many cases and completed by Birkhoff in 1913 shortly after Poincaré’s death the year prior:

Theorem (Poincaré-Birkhoff): An area and orientation preserving, twisting homeomorphism $\psi:A \to A$ on an annulus has at least two geometrically distinct fixed points.

I’ll give some more definitions later on but for now, I want to mention a corollary. For that, we need the following definition: for any kind of self-map $f:X \to X$, a point is periodic if there exists a positive integer $n$ such that $f^n(x)=x$; i.e. $n$ iterates of $f$ brings $x$ back to itself.

Corollary: An area and orientation preserving, twisting homeomorphism $\psi:A \to A$ on an annulus which uniformly twists one boundary component more than the other, has infinitely many periodic points of arbitrarily large period.

In particular, this means that there are infinitely many stable planar orbits for a satellite orbiting in the earth and moon system. This is something that we’re influenced by everyday whenever we make a phone call or GPS or check the weather. All of these systems depend on satellites being in stable orbit around the earth. I will try to outline a proof of this theorem and also the corollary under an additional monotone twisting assumption. We will follow the proof outlined in McDuff-Salamon’s Introduction to Symplectic Topology. They also give a proof for finding at least one fixed point without the additional assumption.

Before doing that, I want to make a few remarks.

- In order to find the direct orbit away from the lunar problem, Birkhoff had in mind finding a disk-like surface of section whose boundary is precisely the retrograde orbit. The direct orbit would then be found via Brouwer’s translation theorem: every area preserving homeomorphism of the open disk admits a fixed point. Removing the fixed point, we obtain an area preserving homeomorphism of the open annulus, which, via a theorem of Franks, admits either none or infinitely many periodic points. Combining these, one has: an area preserving homeomorphism of an open disk admits either one or infinitely many periodic points. Note that if the boundary is also an orbit, we obtain 2 or infinitely many periodic points (not necessarily fixed points). If furthermore we have the twisting, then the Poincaré–Birkohff theorem provides at least two fixed points and also infinitely many orbits.

- The Poincaré–Birkhoff theorem is a paradigmatic result in the following sense. It is easy to state, difficult to prove, none of the assumptions can be removed, and the conclusion is sharp. So in a way, it is optimal and also easy to understand the statement yet the proof is far from trivial. Regarding the assumptions, we can find examples of diffeomorphisms which are missing one of the assumptions and lack fix points. Also, we can form diffeomorphisms satisfying all the properties with exactly 2 fixed points. So we see that each assumption is essential and the conclusion is sharp.

- For an alternative type of proof, we can also use modern techniques of Floer theory. Glue two copies of the annulus together to form a torus $T^2$ which now has a Hamiltonian diffeomorphism $\Psi:T^2 \to T^2$ acting on it, defined by just $\psi$ acting on each annulus. If $\Psi$ is nondegenerate, then by using Hamiltonian Floer theory, we know that the number of orbits is lower bounded by the rank of the homology of $T^2$ which is 4 (this is the Arnold Conjecture, now a theorem). Since $\Psi$ is built from two copies of $\psi$, there must be an even number of fixed points. Since $\psi$ has no fixed points on the boundary (it’s supposed to twist them), the fixed points must be on the interior and there must be at least 2 for $\psi:A\to A$. This technique doesn’t help us understand degenerate Hamiltonians though there is some work in that direction for tori.

Proof of Poincaré-Birkhoff under a monotone twisting condition

Here’s when we follow McDuff-Salamon. Let’s use polar coordinates to describe $A = \mathbb{R}/\mathbb{Z} \times [a,b]$. The homeomorphism $\psi(x,y) = (f(x,y),g(x,y))$ depends on two functions where $f(x+1,y) = f(x,y)+1$ and $g(x+1,y)=g(x,y)$ because of periodicity. Since $\psi$ preserves the boundary components, $g(x,a)=a,g(x,b)=b$. Because it twists the boundary in opposite directions, then let’s suppose that $f(x,a)<x$ and $f(x,b)>x$. So the inner boundary is twisted clockwise (decrease the angle) and the outer boundary is twisted counterclockwise.

Two points $(x,y)$ and $(x’,y’)$ are geometrically distinct if either $y \neq y’$ or $x-x’ \notin \mathbb{Z}$. If we lift $\psi$ to the universal cover $\mathbb{R} \times[a,b]$, then its functions $f’,g’$ will have the same properties as above. Also, the lift satisfies the twist condition and is orientation preserving if and only if it preserves the two boundaries of $\mathbb{R}\times [a,b]$.

The monotone twist condition is the following: if $y<y’$, then $f(x,y)<f(x,y’)$. So if we foliate the annulus into circles of increasing radius, those points lying on circles of larger radii get twisted counterclockwise more than those lying on circles of smaller radii. Note that $\psi$ doesn’t necessarily send these circles to other circles. However, if we draw a straight radial line segment with end points on the boundary, the $\psi$ maps it to some other curve which does not “wiggle” back and forth. Instead, it should be more like a section of a spiral. So then, under this condition, there exists a continuous function $w:\mathbb{R} \to [a,b]$ such that $f(x,w(x))=x$. This function “undoes the spiraling.” Moreover, since $f(x+1,y)=f(x,y)+1$, then $x+1=f(x+1,w(x+1)) = f(x,w(x+1))+1$. So $f(x,w(x+1))=x=f(x,w(x))$. All that to say, $w(x+1)=w(x)$.

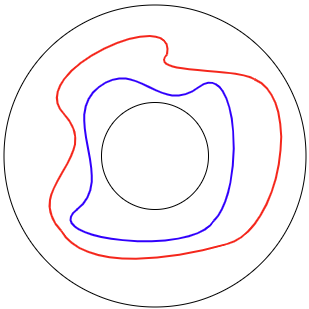

Next, define the closed curve $\Gamma = {(x,w(x)):x\in\mathbb{R}}$. Its image $\psi(\Gamma)$ under $\psi$ must intersect $\Gamma$ in at least two points. To see this, suppose there is no intersection. The picture below shows this hypothetical situation; let the blue curve be $\Gamma$ and the red is $\psi(\Gamma)$. Then the region between the blue curve and the inner boundary is mapped to the region between the red curve and the inner boundary; the area has increased which violates the area preserving property of $\psi$. If they intersect at only one point (a sort of tangency point), the same area argument applies. Of course, it’s also not important that $\psi(\Gamma)$ encloses $\Gamma$; the same argument works if $\Gamma$ were on the outside and $\psi(\Gamma)$ on the inside.

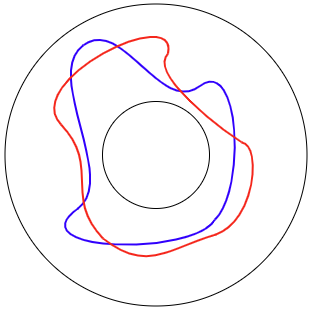

So then the situation must be more like the next picture with at least two intersection points.

Let $(y,w(y))\in \Gamma \cap \psi(\Gamma)$. Then $(y,w(y)) = \psi(x,w(x))$ for some $x$ which means $f(x,w(x)) = y$. However, $w$ has the property that $f(x,w(x))=x$ so we see that $x=y$ and hence, $\psi(x,w(x))=(x,w(x))$. That is, $(x,w(x))$ is a fixed point of $\psi$. Since there were at least two intersection points, we have at least two fixed points. $\square$

Remark: This argument crucially relies on the monotone twisting condition; the preceding argument fails without it.

Corollary of the full Poincaré-Birkhoff theorem: Let $\psi(x,y)=(f(x,y),g(x,y)$ be an area preserving homeomorphism of the annulus satisfying the conditions above on $f,g$. Further suppose that $m = \max_x(f(x,a) -x) < \min_x(f(x,b) -x) = M$. Then $\psi$ has infinitely many geometrically distinct periodic points.

The constant $m$ is the largest angle of rotation for a point on the inner boundary while $M$ is the smallest angle of rotation for a point on the outer boundary. So we want the outer boundary to uniformly be rotated more than the inner one (or vice versa since we can switch their roles).

Proof: Let $f^q,g^q$ denote the 1st and 2nd components of the $q$th iterate of $\psi$. Since the boundaries are preserved, we may write:

\(f^q(x,a)-x = \sum^{q-1}_{j=0}f^{j+1}(x,a)-f^j(x,a)\leq qm.\) \(f^q(x,b)-x = \sum^{q-1}_{j=0}f^{j+1}(x,b)-f^j(x,b)\geq qM.\)

So then, if $q>1/(M-m)$, then $1/q < M-m$. If we think of $1/q$ as the step size, it’s finer than the difference $M-m$. So if we take a bunch of steps, one of them will land between $m$ and $M$; i.e. we can find an integer $p$ so that $m < p/q < M$ and hence, $qm< p< qM$. Using the above inequalities, we have: $f^q(x,a) -x \leq qm < p$ so $f^q(x,a)-p < x$. $f^q(x,b)-x \geq qM > p$ so $f^q(x,b)-p > x$.

Hence, $f^q(x,a) < f^q(x,b)$. So $f^q$ is an area and orientation preserving homeomorphism as well and this inequality shows that it is also a twisting map. Thus, we may apply the Poincaré-Birkhoff theorem to $f^q$ as well to get two fixed points. These two fixed points are periodic points of $f$ with period $q$. Since we only needed $q>1/(M-m)$, we can keep increasing $q$ to get more fixed points for larger iterations of $f$ and hence more periodic points. There may be some overlap and we get the same geometric points but whenever $p/q \neq p’/q’$, we will get geometrically distinct points. For example, there are infinitely many primes larger than $1/(M-m)$. $\square$