Undamped Forced Harmonic Oscillators and Resonance

Published:

I’m teaching an introductory differential equations class this semester and one of the topics is about studying harmonic oscillators in various settings. They’re a great source of 2nd order ODEs and the general form they take is $x’’ + p x’ + qx = f(t)$ where the LHS of the equation comes from Hooke’s Law. For a moment, suppose $f(t)=0$ and $p,q > 0$. Then we have $x’’ = -px’ -qx$; if we think of $x(t)$ as describing the position of some object along a line on a spring with mass normalized to 1, then the $-qx$ term tells us that the force of the spring is always towards the equilibrium position. If $x(t)>0$, this means the spring is stretched and the force wants to pull it back. If $x(t) < 0$, then the spring is compressed and wants to push. Thus, $q$ is called the spring constant. The other constant is related to factors that depend on the velocity. For example, if the object moves quickly, then it may experience greater forces related to friction. Thus, the constant $p$ is called the damping coefficient. When $f(t) \neq 0$, we view it as an extra term telling us how the forces are affected. So we’ll call it a forcing term; note that we’re only asking it to depend on time so it’s an external force that doesn’t care about the position of the object.

To solve the equation, we can do a trick that’s maybe due to Hamilton: introduce another variable $v = x’(t)$. We then find that when $f(t) = 0$, we have on our hands a system of linear equations: \(\begin{pmatrix} x'(t) \\ v'(t)\end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} 0 & 1 \\ -q & -p \end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} x(t) \\ v(t) \end{pmatrix}.\)

The characteristic equation of this matrix is $\lambda^2 + p \lambda + q =0$ which looks a lot like the original ODE; we’ve just traded derivatives for powers of $\lambda$. This is no coincidence, of course. From here, we may find the eigenvalues and eigenvectors and then give a description of the homogeneous solutions to the original ODE. When $f(t) \neq 0$, we then find a particular solution to add to our homogeneous solutions.

Undamped Harmonic Oscillator with Sinusoidal Damping

Let’s make the simplifying assumptions that there is no damping and that $f(t)$ is sinusoidal and in fact, we’ll just assume it’s $a \cos(\omega t)$ or $a\sin(\omega t)$. If we use complex numbers, we can solve both equations at once: $x’’ + qx = ae^{i\omega t}$. The homogeneous solutions come from studying the characteristic equation $\lambda^2 + q = 0$; since $q > 0$, the eigenvalues are purely imaginary: $\pm i\sqrt{q}$. By using Euler’s formula $e^{i\theta} = \cos \theta + i \sin \theta$ and the fact that the real and imaginary parts are individually solutions, the homogeneous solutions are then linear combinations of $\cos(\sqrt{q} t)$ and $\sin(\sqrt{q}t)$.

In order to find a particular solution, we may guess the particular solution should be along the lines of $x_p(t) = \alpha e^{i\omega t}$ where $\alpha$ is undetermined. But plugging this into the equation, we’ll find that we need $\alpha = \frac{a}{q-\omega^2}$. Then, we may take real and imaginary parts, depending on what our forcing term is, to get a particular solution. For example, $\frac{a}{q-\omega^2} \cos (\omega t)$. At this point, we should note that for algebraic reasons, we need $q \neq \omega^2$. This should suggest to us that something interesting is occurring when $\omega \to \sqrt{q}$.

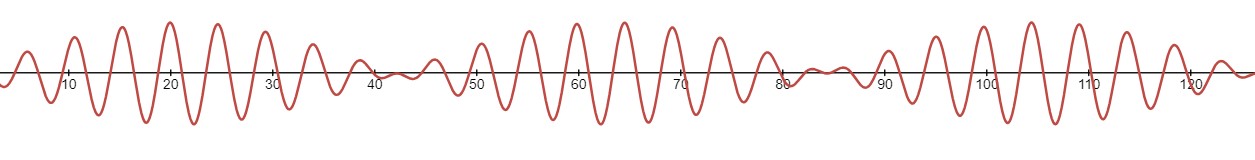

I made an interactive applet using Desmos here (I’m using $x$ in place of $t$ and $t$ in place of $\omega$ in Desmos). Click on the “play button” to see the animation. In the example, $q = 2$ and initial conditions are $x(0) = x’(0) = 0$. So the solution is $\frac{1}{2-\omega^{2}}\left(\cos\left(\omega t)-\cos(\sqrt{2}t)\right)\right)$. Note that $\sqrt{2} \approx 1.414$ and when $\omega = 1.2$, we have the following behavior.

The two cosine functions are constructively and destructively interfering in a way that reveals two kinds of periodic behavior. We have the usual periodicity but now the amplitude of the waves also grow and shrink in a periodic way. Any musician who has played with other musicians know this well; when you’re almost playing in tune with each other but not quite, you hear a sort of pulse of volume. These packets are often called envelopes or wavelets. We’ve been discussing this in the context of a moving spring but hopefully it’s clear that the equations describe a broader range of phenomenon than springs. It can also be applied to radio signals, for example.

Using complex numbers, one can prove that our solution, a difference of cosines, can also be written as a product of sines: $\frac{2}{2-\omega^{2}}\sin\left(\left(\frac{\sqrt{2}-\omega}{2}\right)t\right)\sin\left(\left(\frac{\sqrt{2}+\omega}{2}\right)t\right)$. We may interpret the first sine function (along with the $\frac{2}{2-\omega^{2}}$ coefficient) as describing the amplitude of the second sine function. The amplitude depends on time and is periodic. Note that the frequency of the second sine function is an average of the natural and forcing frequencies.

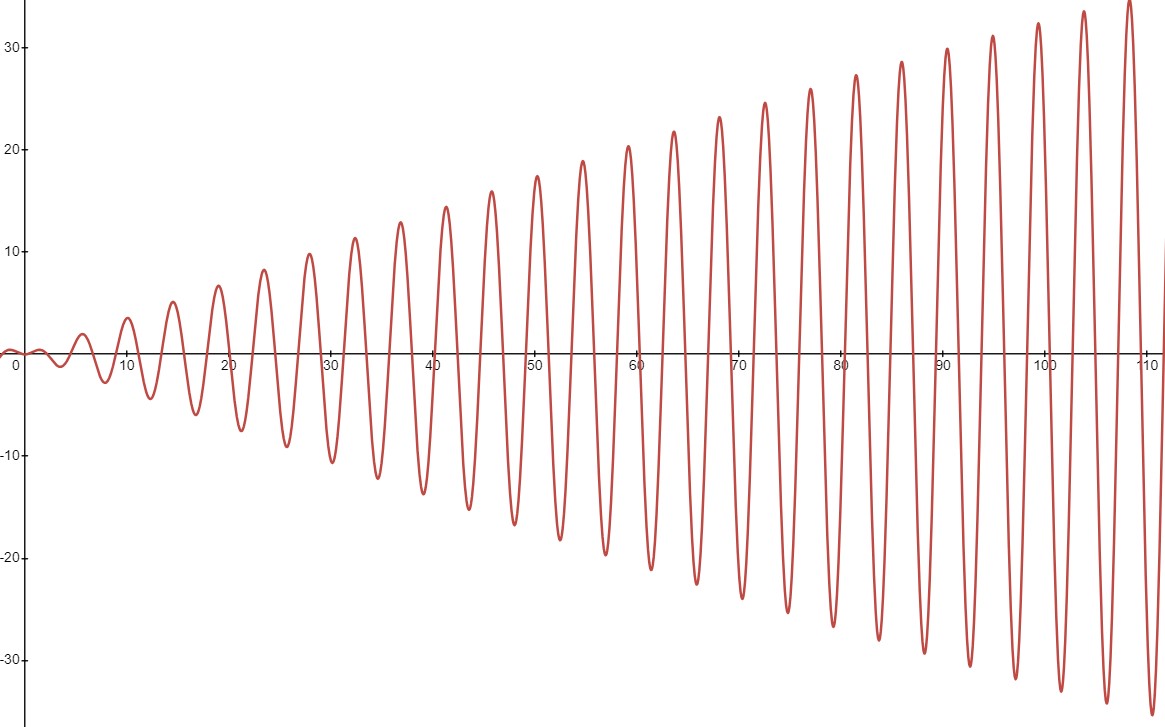

Now, one interesting thing to do is let $\omega \to \sqrt{2}$; we see that the amplitude grows unbounded and in the Desmos link, we find the following at $\omega = 1.4$.

At this scale, it looks like the amplitude is simply growing linearly and unbounded. We need to zoom out quite a bit (to around 450) before we see that we still do have a single wavelet but it’s very large. Also, it’s period is very large. In the limit then, the period goes to $\infty$ which is another way of saying that the amplitude stops having periodic behavior. In order to treat the case when $\omega = \sqrt{2}$, i.e. when the forcing frequency equals the natural frequency of the harmonic oscillator. This special case is called the resonance case and we’ll see that the amplitudes really then grow unbounded. In the context of the harmonic oscillator, this means the spring moves back and forth with ever increasing distance. Of course, when constrained by physical material, the spring would eventually break. Now, to solve the resonant case, we need to make a different kind of guess at our particular solution. This is because, if you still guess $x_p(t) = \alpha e^{i\omega t}$, it’s already covered by the homogeneous solutions and we’ll always get 0 when plugging it into the LHS. Instead, we guess $x_p(t) = \alpha t e^{i \omega t}$. We can then determine $\alpha$ and thus, say exactly how the apparent linear growth should be as $\omega \to \sqrt{q}$.

Millennium Bridge and the Tacoma Narrows Bridge

Now, resonance can be quite a rare phenomenon in nature. Of course, when we’re trying to tune our violins or radio broadcasts, we may see resonance appear and even welcome it. In the latter case, resonance can amplify radio signals. However, if things are occurring randomly, we typically do not expect to see resonance. This is why the story of the Millennium Bridge is so interesting to me. In June 2000, the Millennium Bridge was opened in London, a 350 m footbridge crossing the Thames. However, it was quickly closed because of unexpected horizontal oscillations that were making the bridge unsafe.

Studies then showed a somewhat surprising feature: the bridge was sensitive to horizontal oscillations that occurred at about 1 cycle per second. Since people typically walk about two steps per second, that means the left foot exerts force once a second as does the right foot. This alone should not have much impact since a single pedestrian shouldn’t be exerting enough force to make any noticeable effect on such a large bridge. However, video footage reviewed a second surprising fact: people were walking in time with each other. On opening day, there were as many as 2,000 people on the bridge at once and because of the slight oscillations, people appear to be (unconsciously or not) keeping their balance by timing their steps. Moreover, with such crowds, the walking speed was slower and uniform (no one was sprinting across in those crowds). As a result, the bridge began to experience forcing near the resonant frequency and if kept up, the bridge could have dangerously broken from the force. The bridge was modified and reopened at a later time. One of the modifications was to introduce damping (for us, that means we have a nonzero $p$ term in the equation now).

I want to end by saying again that resonance is still a somewhat rare phenomenon unless artificially introduced. The Tacoma Narrows Bridge was opened in the summer of 1940 but collapsed by the end of that year; there is video footage of it online. In some textbooks on differential equations, the reason for the collapse is cited to be resonance. In the footage, you can certainly see very large oscillations in the bridge; it almost looks like it’s made of rubber. However, mathematician Patrick Joseph McKenna proposed an alternative explanation which can be found here. One of the key points is that the forcing should not be a differentiable function since the cables, when slack due to upward oscillation, contribute no force but when the oscillation goes down, they immediately go taut, contributing a force. So the forcing term is not purely sinusoidal. Personally, I find this to be reasonable but from a cursory look into the history, it does seem that the reasons for the Tacoma Narrows collapse has been hotly debated.