Hamiltonian Dynamics, Periodic Orbits, and the Arnold Conjecture

Published:

Consider the following system of nonlinear ODEs. \(\begin{cases} \frac{dx}{dt} = 2-x-y \\ \frac{dy}{dt} = y-x^2 \end{cases}\)

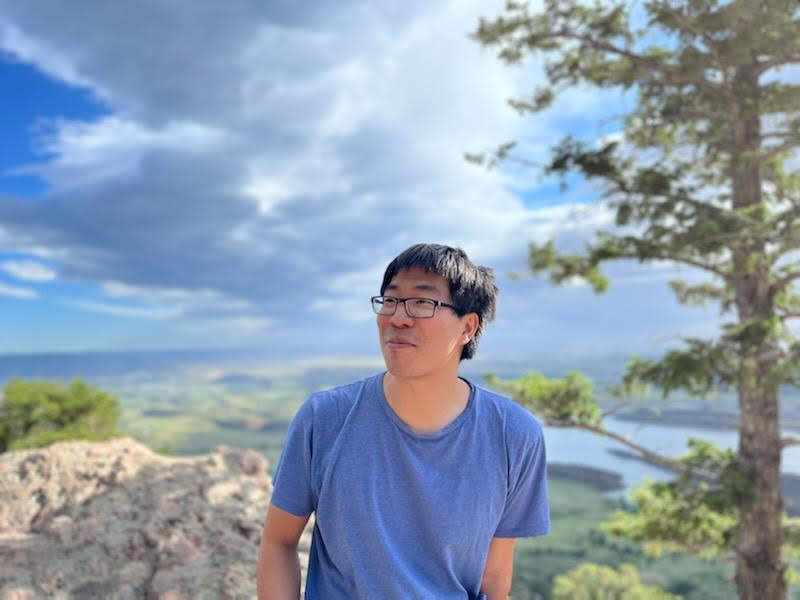

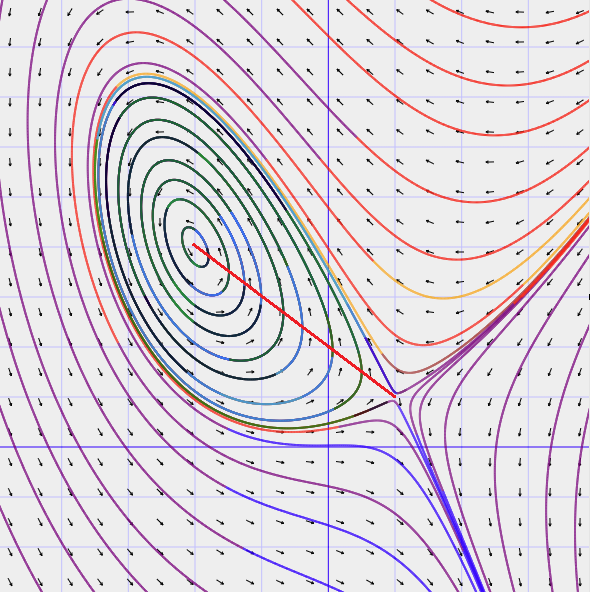

We’ll use this example to illustrate various phenomena in Hamiltonian dynamics and symplectic geometry. We may think of the equations as describing a vector field $X_H$ for us. Here’s a phase portrait (the length of the vectors has been normalized but their lengths should really be varying):

First of all, by setting the equations above to zero, we can find the equilibrium points of this system. We’ll eventually get the equation $2-x = x^2$ and then using $y=x^2$, we have $(-2,4)$ and $(1,1)$ as equilibria (or in other terminology, fixed points of $X_H$). We may linearize the equations at the fixed points by using coordinate changes and then dropping all nonlinear terms.

For $(-2,4)$: We let $u = x+2,v=y-4$ as our coordinate change. Then $(-2,4)\mapsto (0,0)$. Our equations become \(\begin{cases}u' = 2-(u-2)-(v+4) = -u-v \\ v' = (v+4)-(u-2)^2 = -u^2+4u+v \end{cases}\)

To linerize, we only take the linear terms which means we just drop the $-u^2$ so the matrix for this linear system is then \(\begin{pmatrix} -1 & -1 \\ 4 & 1 \end{pmatrix}\)

and its characteristic equation is $\lambda^2 + 3$ which has roots $\pm i \sqrt{3}$. So the equilibrium point is a center and we expect to see solutions that are approximately periodic (if not actually periodic).

For $(1,1)$: We let $u=x-1,v=y-1$ and the equations become \(\begin{cases} u' = 2-(u+1)-(v+1) = -u-v \\ v' = (v+1)-(u+1)^2 = -u^2-2u+v \end{cases}\)

To linearize, we again drop the $-u^2$ term and the matrix for the linear system is then \(\begin{pmatrix} -1 & -1 \\ -2 & 1 \end{pmatrix}\)

and its characteristic equation is $\lambda^2 - 3$ which has roots $\pm \sqrt{3}$. So the equilibrium point is a saddle point since these are real eigenvalues of opposite parity.

The separatrices are the solution curves which tend to the saddle point when $t \to \pm \infty$. Note that they look like a nodal cubic (algebraic variety) defined by, say, $y^2 = x(x-1)^2$, albeit with a bit of distortion.

Another thing to notice is that there seems to be a whole infinite family of periodic orbits here; if we connect the two equilibria by a red line segment as shown in the phase portrait, there is a distinct periodic orbit passing through every point on the line segment (including the endpoint equilibria which can be thought of as periodic orbits with period 0 since they’re constant).

Symplectic Geometry and Hamiltonian Dynamics

Note that if we let $H(x,y) = \frac{x^3}{3}-xy+2y-\frac{y^2}{2}$, then $x’(t) = \partial_y H, y’(t) = -\partial_x H$; the form that these equations are taking are called Hamilton’s equations (I just mean that there’s nothing special about this $H$ to give it the name “Hamilton”; it’s more about what we do with $H$). So the dynamical system is called Hamiltonian and these appear a lot in classical mechanics.

To flesh this out a bit, we may equip $\mathbb{R}^2$ with a symplectic form which is a closed, nondegenerate differential 2-form $\omega$. More generally, many smooth manifolds can be equipped with such a symplectic and we would denote the pair as $(M,\omega)$. Closed means $d\omega = 0$ and being nondegenerate means it gives an isomorphism between vector fields on $M$ and differential 1-forms on $M$. In a way, a symplectic manifold can be viewed locally as being a phase space which tracks the position and momentum of moving objects. The Hamiltonian $H$ tells us about the total energy and the Hamiltonian vector field $X_H$ tells us about how the classical system evolves over time. One consequence is that if $H$ is independent of time (called autonomous), then things should evolve in a way such that energy is conserved. A level set $H^{-1}(E)$ is thought of as the set of points that fall into a certain energy level $E$. So the evolution must occur within the energy level; we cannot have points moving from one energy level to another because that breaks conservation.

In our case, we’ll use the standard symplectic form $\omega = dx\wedge dy$ and it’s convenient at this time to note that if we let $\lambda = x \, dy$, then $d\lambda = \omega$. In particular, we see that $\omega$ is closed since it is exact.

The isomorphism alluded to above is one given by contraction. For example, $\iota_{X_H} \omega = \omega(X_H,-)$ which is a 1-form. The fact that $X_H$ satisfies the equations above related to $H$ means that in fact, $\iota_{X_H} \omega = dH = \partial_x H\, dx + \partial_y H \, dy$. That is, the 1-form we get is in fact an exact 1-form coming from $H$.

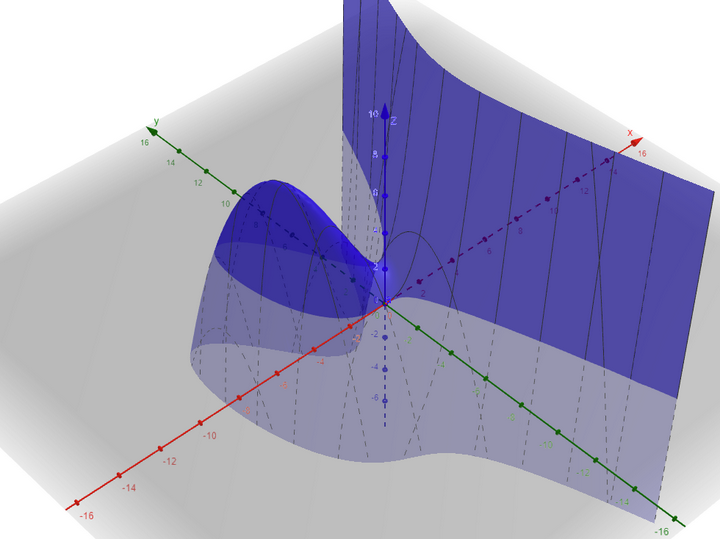

So as a reminder, $X_H = x’(t) \, \partial_x + y’(t) \partial_y$, where the $x’(t),y’(t)$ are equal to what we wrote at the start and again, the Hamiltonian equations we want to satisfy are $x’(t) = \partial_y H, y’(t) = -\partial_x H$. Then, the integral curves for $X_H$ shown above are containted in the (energy) level sets of $H$. Since the dimensions here are low, the geometric integral curves coincide with the level sets.

Note that $H$ is also a Morse function. To check this, we see that its critical points are exactly the equilibria and its Hessian is \(\begin{pmatrix} 2x & -1 \\ -1 & -1 \end{pmatrix}.\)

For $x=-2, 1$, the Hessian is nondegenerate because the determinant is nonzero. Also, the norm of the Hessian at these points is smaller than $2\pi$ so this $H$ is considered to be $C^2$-small which means that the notion of nondegeneracy of critical points in the Morse theoretic sense coincides with the notion of nondegeneracy for periodic orbits in the Floer theoretic sense. The former sense is just what I’ve said about the Hessian; the latter sense is where we take the time $T$-flow $\psi_T$ and find its fixed points; these correspond to orbits with period $T$. For an orbit $\gamma$ to be nondegenerate, we require the linearization $D_{\gamma(t)}\psi_T$ to not have $+1$ as an eigenvalue.

The critical point $(-2,4)$ has index 2: i.e. is a local maximum. At $(1,1)$, the critical point has index 1 as we know since it’s a saddle.

Energy Level Sets

Here is a graph of $H$; we can see the shape of it fits well with the level sets.

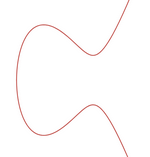

So some of these level sets will roughly appear as:

These previous ones have lower energy than these next ones:

For these, note we’ll have a periodic orbit as well as a nonclosed trajectory in the same energy level. Lastly, these nonclosed trajectories have the highest energy.

But also, $H$ is an autonomous Hamiltonian. From a physics perspective, this means that energy is not conserved within the system but rather there may be some energy entering or leaving the system. One implication of having an autonomous Hamiltonian is that any nonconstant periodic orbit is automatically degenerate. This fits with our situation: the nondegenerate orbits should be isolated and here, the nonconstant periodic orbits are not isolated and hence, must be degenerate. But I’m actually being a bit imprecise here since, though we have many periodic orbits, it might not be that they all have the same period.

Periods

So let’s discuss periods. We will define the action of an orbit $\gamma$ and we’ll show it is related to its period. First, we will use our 1-form $\lambda =x\,dy$ from earlier.

The first claim is that there is a function $\alpha:\mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R}$ such that $\alpha \circ H$ has the same geometric periodic orbits as $H$ (it may change some of the nonclosed trajectories) but makes all the periodic orbits have period $2\pi$ (see Ch. 1 of Jonny Evans’ book Lectures on Lagrangian Torus Fibrations). The way to prove this claim is to use the following theorem:

Theorem 1.6 (Evans’ book): In a 1-parameter family of orbits $\gamma_b$ where $b \in \mathbb{R}$, we have a function $f:\mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R}$ given by $f(b) :=\int_{\gamma_b} x \,dy$. Then the period of $\gamma_a$ is given by $f’(a)$.

So the function $\alpha$ we wanted for making all the periodic orbits have period $\pi$ can be defined as $\alpha(b)=\frac{1}{2\pi}f(b) = \frac{1}{2\pi}\int_{\gamma_b}x \, dy$. Depending on conventions, one might call $\alpha$ the action or perhaps $f$ is the action; they only differ by a factor of $2\pi$. Note that $\alpha(b)-\alpha(b_0) = \frac{1}{2\pi}\int_{\gamma_b-\gamma_{b_0}}x \, dy = \frac{1}{2\pi}\int_{C_b} dx \wedge dy$ where $C_b$ is the cylinder made from the orbits that connect $\gamma_b$ and $\gamma_{b_0}$. If we choose $\alpha(b_0)=0$, then the function $\alpha(b)$ just gives the area of the cylinder connecting $\gamma_b$ and $\gamma_{b_0}$, divided by $2\pi$.

In this way, we see that the original periodic orbits really do have different periods. The Mean Value Theorem says that there exists a $c \in [b_0,b]$ such that $f’(c) = \frac{f(b)-f(b_0)}{b-b_0}$; and we’d set $f(b_0)=0$ earlier so then it’s just $f’(c) = \frac{f(b)}{b-b_0}$ which is the area of the cylinder $C_b$ divided by $b-b_0$.

So after postcomposing with $\alpha$, we have that $\alpha \circ H$ has a 1-parameter family of degenerate orbits all with period $2\pi$. As such, this example is not immediately ammenable to the standard Floer theory that Floer himself developed.

The Arnold Conjecture and Hamiltonian Floer Theory

The aforementioned Floer theory begins by building a chain complex over a ring $R$ generated by the periodic orbits of a nondegenerate Hamiltonian or equivalently, fixed points of the time-1 flow $\psi_1$ (we just normalize to time 1). In particular, there are finitely many of them and they can be assigned an index to be used for getting different degrees of the chain complex. The differential is then a count of solutions to a perturbed Cauchy-Riemann type equation called the Floer equation where the domain is $\mathbb{R} \times S^1$. These are cylinders and we require that they have finite energy and limit to the orbits. So one should think of the cylinders as connecting two orbits. The homology of the complex is what’s known as the Hamiltonian Floer homology. What is the point of creating such an algebraic object? Through some spectacular analysis on the part of many people, this type of homology is used to give a positive answer to Arnold’s Conjecture for all closed symplectic manifolds.

Arnold’s Conjecture (now theorem): Let $(M^{2n},\omega)$ be a closed, symplectic manifold and let $H$ be a (possibly) time-dependent, nondegenerate Hamiltonian. Let $R = \mathbb{Q}$ or a finite field like $\mathbb{F}_p$. Then the number of periodic orbits for $H$ is lower bounded by the sum of the Betti numbers of $M$ over $R$; i.e. there are at least $\sum_i^{2n} b_i(M,R)$ orbits.

First of all, the nondegeneracy condition is generic and so the theorem applies to “most” Hamiltonians. The statement is also rather remarkable because from classical topology, the number of fixed points of a self-map on $M$ has lower bound being the alternating sum given above which is the Euler characteristic $\chi(M) = \sum (-1)^i b_i$. So somehow, symplectic manifolds and these kinds of Hamiltonian diffeomorphisms $\psi_1$ are special in that they generate more periodic orbits. Floer’s idea for proving the conjecture goes roughly as follows. We first want to obtain Hamiltonian Floer homology $HF_*(M,H)$ which in a very rough sense, is an attempt to do Morse theory using an action functional that is, in a way, similar to the action defined above but whose domain is on the loop space of $M$. Since this is an infinite-dimensional space, much care must be taken. In order to define the differential $\partial$, one must study the solutions to the Floer equation and prove three key results about the moduli space of solutions: transversality to get a smooth manifold, compactness in order to have a sensible way to make “counts”, and gluing in order to prove that $\partial^2 = 0$. Only then do we have a well-defined homology. After this, we need to show that $HF_*(M,H)$ is actually independent of the nondegenerate Hamiltonian; i.e. if we choose another nondegenerate Hamiltonian, we’ll get the same answer. Due to this invariance property, in particular, if $H$ is a $C^2$-small Morse function, then $HF_*(M) \cong HM_*(M) \cong H_*(M)$; i.e. we get an isomorphism through Morse homology to singular homology.

The theorem above was proved over the course of many years with contributions from many people. I’m afraid I will miss some contributors but I’ll make an attempt to give some history. Conley and Zehnder first proved the conjecture for surfaces with genus at least 2 and for certain classes of Kähler manifolds, without any kind of homology theory. After this, Floer introduced his Hamiltonian Floer homology and proved the conjecture for so-called monotone symplectic manifolds. Later, Hofer–Salamon and Ono proved the conjecture for all so-called semi-positive symplectic manifolds over coefficients $R=\mathbb{Z}$. For general symplectic manifolds, Fukaya–Ono, Liu–Tian, and Ruan proved the Arnold conjecture with lower bound coming from the $\mathbb{Q}$-Betti numbers. These papers are based “virtual techniques” which are very powerful but have witnessed certain drama and controversy in the past. Personally, I think that by now, those concerns have been properly addressed.

For $R=\mathbb{F}_p$, we turn to the work of Abouzaid–Blumberg which relies heavily on stable homotopy theory and Morava K-theory and produces lower bounds on the number of periodic orbits by the sum of Betti numbers in any finite field. The reason for needing to appeal to Morava K-theory is because, as we count the solutions to the Floer equation, there may be finite stabilizer groups of order being a multiple of $p$; we would want to then divide by that order. However, if we use $\mathbb{F}_p$ coefficients, $p \equiv 0 \pmod{p}$. Hence, the appeal to Morava K-theory $K_p(n)$ where, for large $n$, we approximate $\mathbb{F}_p$.

Lastly, we now have sharper lower bounds over $\mathbb{Z}$ provided by Bai-Xu.

Back to Our Example

For our example from the start, we face an issue: $\mathbb{R}^2$ is an open manifold which makes it not closed; i.e. either not compact or has boundary. We also see a second potential issue. When $H$ is postcomposed with $\alpha$, we would have infinitely many periodic orbits of period $2\pi$. We can’t generate a chain complex using every orbit as generator; that would be too big of a chain complex. One sort of maneuver to address the openness issue is to use a new (co)homology theory called symplectic cohomology. For the 1-parameter family, we might use a Morse-Bott version. If we don’t postcompose with $\alpha$, naively, we might treat $H$ as a $C^2$-small Morse function and compute its Morse homology. But the openness of $\mathbb{R}^2$ makes it so that the Morse homology of our particular $H$ does not give the singular homology of $\mathbb{R}^2$. If you try it with $\mathbb{Z}$ coefficients, you get $HM(\mathbb{R}^2,H) = 0$ rather than $\mathbb{Z}$. Thus, though $\mathbb{R}^2$ is very simple in a way, this example also demonstrates some of the peculiar phenomena that can quickly arise.