Two Elegant Proofs of the Pythagorean Theorem

Published:

In this post, I’ll like to provide two proofs of the Pythagorean theorem which I find elegant and also, don’t really require anything other than pictures though, of course, I’ll discuss them with words. Now, recall that if we have a right triangle in the Euclidean plane with side lengths $a,b,c$ where $c$ is the length of the hypotenuse (the longest side), the Pythagoreans understood that the three numbers are related to each other by the equation $a^2 + b^2 = c^2$.

First Proof

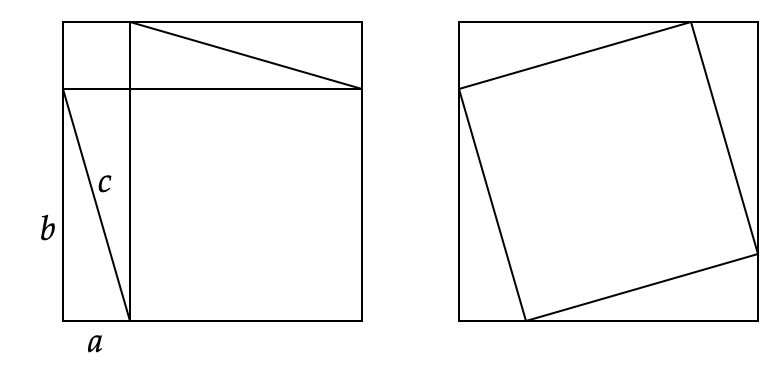

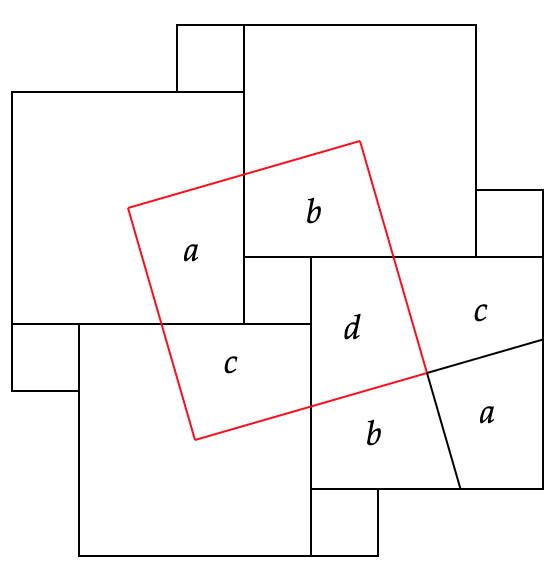

I’ve been told that this proof was known to the ancient Chinese. I’ve labeled the side lengths but the picture could have gone without them. See if you can understand why $a^2+b^2=c^2$ before going ahead for an explanation.

The left image is of a square with side lengths $a+b$ and so we can fit in a square of side length $a$ and a square of side length $b$ into it, as depicted. There is then some left over area which I’ve divided into four triangles. These triangles are copies of the right triangle mentioned above. In the right image, we have the same large square of side length $a+b$. Inside of this large square, we again have our right triangle and we put a tilted square of side length $c$ inside. What we find is that if we remove this square, we’re left with four right triangles, again copies of the right triangle from before. They’re arranged differently than in the left hand image but they have the same area. So then, in both images, the largest outlining squares have the same area and if we remove the four triangles in each image, we must be left with the same area. One representation of the area is as the sum of the areas of two squares of side lengths $a$ and $b$ (left side) and another representation is as the area of one square of side length $c$ (right side). So the areas are $a^2+b^2$ for the left, $c^2$ for the right and they must equal.

I like a proof without lots of symbols. Though I didn’t take high school geometry, I’ve tutored the subject and students sometimes are confused or at least find it dry to start with axioms and build up a bunch of lemmas and propositions using two-column proof styles. There’s nothing wrong with doing geometry in this manner but I suspect that Euclid wrote The Elements to be academically rigorous; he probably didn’t imagine teenagers learning geometry in the style of his writing. Or perhaps he did but educated teenagers in ancient Greece were carefully selected and had more intensive preparation leading up to geometry. If I may continue in this side tangent, in Plato’s Meno, Socrates presents an uneducated slave boy with a square and asks him to construct a new square from it with double the area. With some minor but verbose—as Socrates is—guiding questions, the boy has a lightbulb realization that he must use the diagonal of the original square. Socrates concludes that learning is not about acquiring new information but rather about remembering innate knowledge that the soul already possessed. He calls this anamnesis or recollection. While I do think learning involves acquiring new information, I do think this Socratic method of guiding students to realize for themselves is highly valuable.

Second Proof

I learned this proof from Roger Penrose’s The Road to Reality though I don’t know if this proof originates with him; I doubt it, only because the Pythagorean Theorem has been known for millenia. He wrote the book a long time ago, well before he was awarded a Nobel Prize in physics.

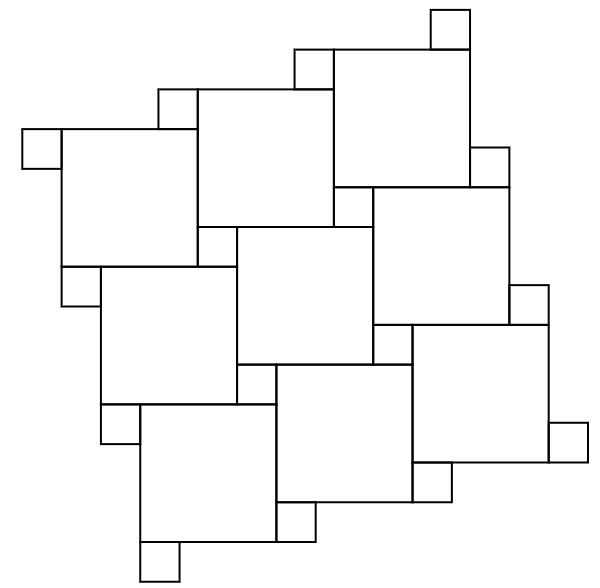

Let’s begin with a seemingly unrelated question. Given two squares, can we use copies of them to tile the plane? The only rule is that we must use both of them because, of course, with just one square, we can make a square grid that tiles the plane. So then, this question is not so interesting if the two squares are the same size. You can give it a try yourself before reading on.

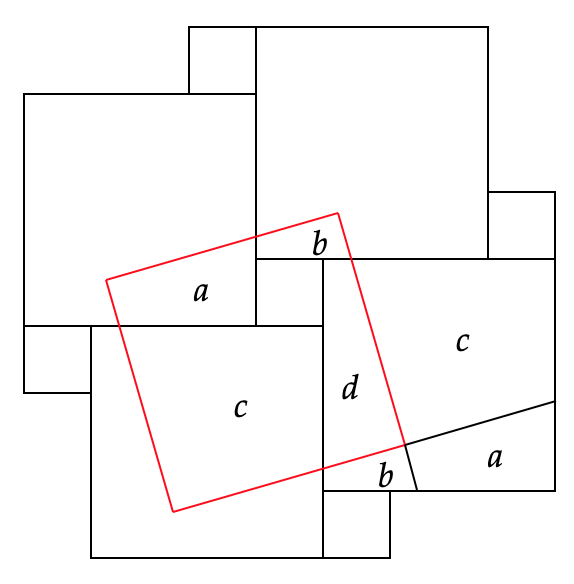

At first, I thought that it might be important for the ratio of the side lengths of the two squares to be a rational number. But that was just overcomplication. One solution is to use what’s shown in the picture below and extend it indefinitely. And this is no secret tiling since I’ve seen bathroom floors tiled this way before. So let’s call it a two-square bathroom tiling.

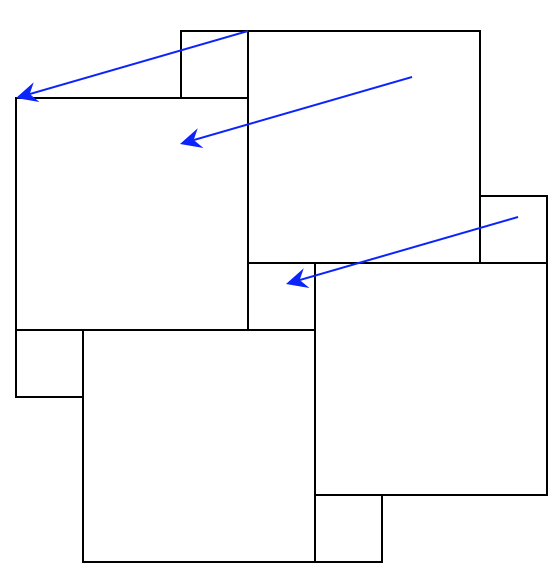

Now, let’s zoom in a bit on a particular portion and draw a blue arrow from the corner of the smaller square to a corner of the larger square. Note that if we pick a point in the smaller or larger square and we move it the distance and direction prescribed by the blue arrow, we get the same point as we started with! Or rather, the head of the arrow lands on a point that is in the exact same position relative to the square it’s in as the point at the tail within the square that it’s in. In other words, if we translate the whole plane with this particular tiling via the blue arrow, it would appear as if we’ve not done anything because the tiling will be shifted in such a way to land perfectly on itself. And though I didn’t depict it, there is another blue arrow of the same length but at a right angle to the one shown which also gives a translation so that it would appear as if we did nothing at all.

Let’s now make a tilted red square which is formed by connecting the midpoints of four of the larger squares.

First, note that the side length of the red square is the same length as the blue arrow. Also note that the red square contains a copy of the little square plus some quadrilaterals which I’ve labeled $a,b,c,d$. Moreover, if we move down and over a bit to consider one of the large squares, we see that it can be built exactly out of a rearrangement of these four regions $a,b,c,d$. So the area of the tilted red square is the area of the small square plus the area of the large square! This is another proof of the Pythagorean Theorem.

In fact, note that we could move the red square around so that it’s vertices aren’t on the center of the large square but anywhere you like. You can still arrange for the tilted red square to be built from a small square and four additional pieces which are no longer identical to each other after rotating and translating. But no matter, we can still rearrange them to build the large square.

This second proof uses more ideas than necessary, since we didn’t need to tile the plane at all in the first proof, for example. But I like it more because it introduces the concept of symmetries which is about the following. If you perform some action in geometry and find that the action appears to not have done anything at all to the overall picture, then the action is called a symmetry. In our example, the tiles are all shifted in the direction of the blue arrow so there has been a change but if you show your friends a before and after picture of the tiling, they could not distinguish the two. I also like this proof because it illustrates that the placement of the tilted red square is not all that important though if you pick the center of the large squares as vertices for the tilted red square, then you get some extra symmetry; namely, you can rotate the red square by $\pi/2$ and each quadrilateral would land on top of the next one.

If we use the tilted red square, we can make a tilted red grid of the whole plane and the two directions of the red grid would tell us exactly which translations preserve the two-square bathroom tiling. If those directions are $\vec{v},\vec{w}$, then any integer linear combination of them $m\vec{v}+n \vec{w}, m,n \in \mathbb{Z}$ would give an arrow that gives us a translational symmetry. Hence, the group of translational symmetries of this two-square bathroom tiling is isomorphic to $\mathbb{Z}\oplus \mathbb{Z}$. Of course, if the squares change, so does the tiling and hence, the red grid would change. But abstractly, all of them have isomorphic grids. If we let the smaller square shrink, then in the limit as it shrinks to a point, the red grid would become the untilted Cartesian grid we usually think of. So this procedure plus dilating gives a geometric and continuous way to establish an isomorphism between all the groups of translational symmetries for all the different two-square bathroom tilings. In fact, we can even apply this to certain two-rectangle bathroom tilings but of course, those won’t provide a proof of the Pythagorean Theorem.