Integrability and the Three Body Problem

Published:

The standard definition for integrable system, which, for example, can be found on the Wikipedia article, is due to Liouville. Given a Poisson manifold $(P,\{ \})$ parametrising the states of a mechanical system, a Hamiltonian function $H$ defines a vector field $X_H := \{H,-\}$, whose flows are the classical trajectories of the system. A function $f$ which Poisson-commutes with $H$ is constant along the classical trajectories and hence is called a conserved quantity. For example, if $(P,\omega)$ is a symplectic manifold, then there is a Poisson bracket given by ${f,g} = \omega(X_f,X_g)$ where $X_f,X_g$ are Hamiltonian vector fields; i.e. $\iota_{X_f} \omega = df$ and similarly for $g$. Note that $\{f,H\} = \omega(X_f,X_H) = df(X_H)$ and so if this is zero, then $f$ is constant in the direction of $X_H$ which are the classical trajectories.

The Jacobi identity for the Poisson bracket says that if $f,g \in C^\infty(P)$ are conserved quantities, then the function ${f,g}$ is also conserved. Two conserved quantities are said to be in involution if they Poisson-commute and the system is said to be classically integrable if it admits “as many as possible” independent conserved quantities $f_1,f_2,…$ in involution. Independence means that the set of points of $P$ where their derivatives $df_1,df_2,…$ are linearly independent is dense.

If $(P^{2n},\omega)$ is finite-dimensional and symplectic, then “as many as possible” means $n$. (One may include $H$ itself among the conserved quantities). However there are interesting infinite-dimensional examples (e.g. Korteweg-de Vries hierarchy and its cousins or symplectic field theory) where $P$ is only Poisson and “as many as possible” means in practice an infinite number of conserved quantities. Also it is not strictly necessary for the conserved quantities to be in involution, but one can allow the Lie subalgebra of $C^\infty(P)$ that they span to be solvable but nonabelian.

The Three Body Problem

One of Poincaré’s big claims to fame was a proof that the planar three-body problem is not completely integrable (found in Les Methodes Nouvelles de Mecanique Celeste). Specifically, Poincaré proved that besides energy, angular momentum, and linear momentum there are no other nonconstant analytic functions on phase space which Poisson commute with the energy. These other functions would be linear combinations of the three. His proof, or its extensions, only holds in the parameter region where one of the masses dominates the other two so it is possible that for very special masses and angular momenta/energies, the system is integrable but probably no one believes that this would be true.

Poincaré’s impossibility proof is based on his discovery of a homoclinic tangle embedded within the restricted three body problem, viewed in a rotating frame. To discuss this, we need some setup.

Definition: Let $f:M \to M$ be a $C^k$-homeomorphism on a $C^k$-manifold $M$ with a fixed point $p$. Then the stable set is defined as $W^s(f,p) := \{q \in M:f^n(q) \to p \text{ when } n \to \infty\}$. The unstable set is $W^u(f,p) := \{q \in M:f^{-n}(q) \to p \text{ when } n \to \infty\}$. When $k \geq 1$, it can be shown that the stable and unstable sets are locally $C^k$-embedded disks. This definition involves a discrete notion but is much like the gradient flows of Morse theory.

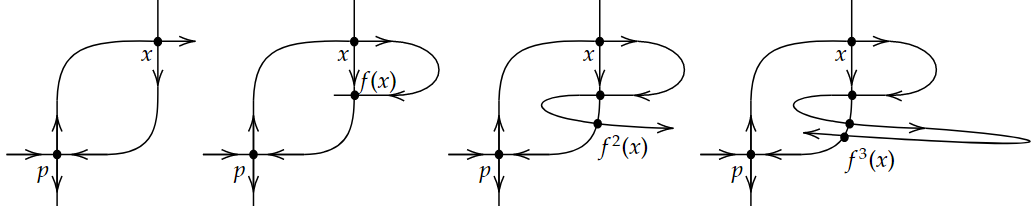

If $V$ is a connected manifold invariant under $f$ and is contained in the intersection $W^s(f,p) \cap W^u(f,p)$, we call it a homoclinic connection. If we have a different fixed point $q$ and $V \subset W^s(f,p) \cap W^u(f,q)$, we call it a heteroclinic connection. If there is no such $V$ (for a single $p$), a different kind of structure appears which is called a homoclinic tangle. Let’s consider the behavior on a symplectic 2-manifold $(M^2,\omega)$ (not necessarily compact) and suppose that $f:M \to M$ is a symplectomorphism. The picture below shows four iterations of $f$ (starting at 0).

Here, $p$ is a fixed point and since this is area preserving, the linearization of $f$ is in the symplectic group which, in dim 2, is $SL(2,\mathbb{R})$; i.e. the eigenvalues are $\lambda,\lambda^{-1}$ and so we have a contracting and expanding direction (unless $\lambda = \pm 1$). The curves above are the stable and unstable sets which are locally disks. Suppose that the stable and unstable sets intersect somewhere, at a point $x$ that is not a fixed point. Then, if we apply $f$, that means that $x$ wants to be “flowed discretely” in two distinct directions. The only way for this to happen is for $f(x)$ to also be in the intersection $W^s \cap W^u$. Moreover, at $f(x)$, there should again be flows going in two distinct directions. So if we keep applying this reasoning, we see that all the iterates $f^n(x)$ have to lie in the intersection $W^s \cap W^u$. But also, $x \in W^s$ so $f^n(x) \to p$ as $n \to \infty$. Moreover, the distance between each successive iterate is getting smaller as we accumulate near $p$. Since $f$ is area preserving, when a rectangle gets thinner, it has to be longer in order to have the same area. So there is a “tangle” that oscillates very wildly as things get stretched. This shows that near a fixed point $p$, it becomes extremely chaotic. Here’s a picture which can be found in Galileo Unbound by David Nolte and also this link.

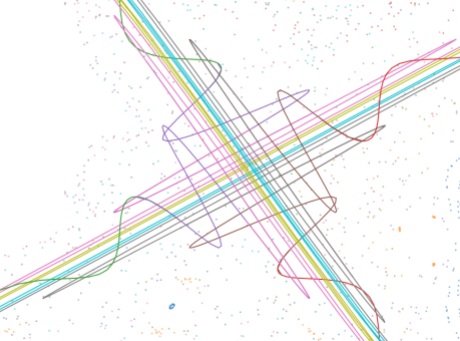

In this tangle, the unstable and stable manifold of some point $p$ (an orbit in the non-rotating inertial frame in the three-body problem) cross each other infinitely often, these crossing points having the point $p$ in its closure. I’m not sure how to show that such an $x$ exists in the first place but if you have it, then you’ll get the tangle.

Poincaré showed that an additional conserved quantity would have to be constant along this complicated set which accumulates at $p$. Analytic functions have the property that if they’re constant on a sequence of points accumulating somewhere, then the whole function is in fact, constant.

Rings of Saturn

To conclude, I’ll like to discuss another example where these ideas of stable and unstable manifolds show up in astrophysics. The Wikipedia article on stable manifolds gives the rings of Saturn as an example. To paraphrase it, the gravitational tidal forces coming from Saturn are such that they flatten the debris into the equatorial plane (so contraction in one direction) even as they stretch it out in the radial direction (expanding). So mathematically, this is what a matrix of $SL(2,\mathbb{R})$ does since it has eigenvalues $\lambda,\lambda^{-1}$ and so long as their norm isn’t 1, we’ll have the contraction and expansion behavior.

Moreover, if there are any perturbations that push particles in the rings above or below the equatorial plane, the particle will actually feel a restoring force, pushing it back into the plane. Thus, it’s not possible for a planet such as the one in the Disney movie “Treasure Planet” to have multiple rings in different equitorial planes, at least not stably over the long term. On the other hand, similar to the chaos of the planar three bodies discussed above, if one were to track the movement of particles, it would also be chaotic.